Umbria is the only region of peninsular Italy that doesn’t have any coastal areas or exits to the sea. The territory is predominantly constituted of mountainous and hilly areas, and one of the main characteristics of the region is the almost total absence of plains.

Because of the peculiar landscape, the region boasts the presence of abundant wooded areas that represent almost 30% of the total area. The woods, together with the widespread olive groves characterize Umbria as a “green region,” one of the most beautiful in the whole country.

Although located in the middle of the peninsula, Umbria has a somehow tormented history and it has always been rather isolated compared to the adjacent regions. This peculiarity explains why Umbria has little to do with the main Italian commercial routes and it is also one of the reasons why in the region was favored for the preservation of traditional features and agricultural landscapes.

On the other hand, this isolation from the commercial routes also prevented the emergence of industrial activities in the main centers, especially in the provincial capitals.

The name of the region, Umbria, dates back to antiquity and is due to the Umbrian, a prehistoric civilization that inhabited the Apennine region between the river Tiber and the Adriatic Sea.

The history of the region is often shadowed in a national context by the history of the adjacent, more powerful regions. Nevertheless, at the time of the unification of Italy, Umbria also included the western part of the current province of Rieti. The territory was surrendered to Lazio in 1923, and Rieti became a province in 1927. In the same year Terni was also established, which is the second province of Umbria.

Prehistory of Umbria

The Umbrian prehistory is not documented in detail, although sporadic materials referable to the lower Paleolithic industries were reported in some surface collections, especially in the province of Perugia. These remains were found in the late nineteenth century and in the early decades of the twentieth century.

Noteworthy are some findings belonging to the Acheulian and Mousterian industries that were found in Abeto in the province of Perugia and in Orvieto, which is part of the province of Terni.

A complex of the upper Paleolithic is also present in the layers of the Tane del Diavolo cave, near Parrano. The so-called “Venere del Trasimeno” is an important artifact consisting of a small fragment of steatite measuring less than two inches and that is statistically attributed to the upper Paleolithic era. The peculiarity of this fragment is that it was discovered on the surface, outside the stratigraphic context.

More abundant are the remains belonging to the Neolithic and Iron Ages. Extensive testimonies from the end of the Bronze Age and from the first decades of the Iron Age come from numerous necropolises such as Monteleone di Spoleto and Panicarola, but also from sites such as Piediluco.

The so-called necropolis of the “Acciaierie di Terni” is rich in tombs built for cremated bodies, then for burial rituals, there are tombs dating from the tenth to seventh centuries BC.

It is also noteworthy to mention the remains of an abode and a necropolis that seems to belong to the fifth or fourth century BC. The remains were found during excavations at Colfiorito and are corresponding to the ancient center of Plestia.

History of Umbria

The history of Umbria begins with a blend of various populations that were disputing their supremacy in the region. In fact, Umbria was divided between the Etruscans on the territory to the right of the river Tiber, and the Umbri, a civilization inhabiting the area between the left bank of the Tiber and the Adriatic coast.

The most important Etruscan settlements were Orvieto and Perugia, while Gubbio was one of the main Umbrian centers. In the third century BC, the Romans turned their interest towards the region, while their interest was at the same time attracted by Etruria.

In 295 BC, as a result of the Battle of Sentinum, the Umbrian fell under the domination of Rome, which strengthened its presence in the region by establishing the colony of Spoleto and by starting the construction of Via Flaminia.

Under the Augustan division of Italy in the first century BC, Umbria became the VI region which included the Adriatic area called ager Gallicus. United to the Etruria under the reformation of Diocletian and after the collapse of the Roman empire, Umbria became the scene of the battles between the Goths and the Byzantines during the Gothic War. During the war, the region suffered serious devastation.

After the conquest of the Longobard, Umbria’s territory was included in the Duchy of Spoleto, founded by Faroald in 570 AD. The Byzantine defense has its center in the Apennines, and the towns of Cortona, Orvieto, Chiusi, and Orte were all involved in the military events.

Concluding the Gothic War, Umbria became a corridor between Rome and Ravenna, with Perugia being the most important center along the way.

The territorial division of the region was definitively ratified in 598, when the peace treaty divided Umbria into two distinct political areas, an eastern one which was part, at least until the twelfth century, of the Duchy of Spoleto, and a western part, also called the Roman Tuscia, which became part of the Pontifical State after the loss of the Byzantine unity.

Following the Carolingian dynasty, Umbria entered into a period of profound anarchy. The situation in the region was characterized by autonomous local realities dictated by the papacy and the empire. In the eleventh century, the diffusion of the municipalities increased the political and economic significance of the region that, for a short period of time, became more important than Tuscany.

In 1198, Pope Innocent III succeeded in imposing his authority on the region and replaced the Duke of Spoleto with a rector. In the following era, Umbria witnessed a strong demographic growth that was accompanied by a discreet economic development favored by the revival of agriculture and trade.

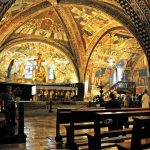

In the thirteenth century, the religious phenomenon of Franciscanism gave rise to a proof of integration between the various cities of Umbria. The conflicts between laics and the Church were long, and in the end, the church managed to prevail over the communes in the second half of the fourteenth century.

The victory of the church was entirely based on the agile policy of Cardinal Egidio Albornoz. The vicissitudes of the commune of Perugia, based on a solid economic strength, were at the center of the trade between the Adriatic Sea and Florence. As a result, Pope Urbano V succeeded in imposing his will in 1370, but the inhabitants of Perugia rebelled in 1375 and restored the popular government.

As a consequence of the following events, Perugia was then troubled by the succession of the noble domination that was always counterattacked by the city’s defense. In the first half of the sixteenth century, the city was conquered once again by the papal army. The same happened to other cities in the region, such as Foligno, occupied by the forces of Eugene IV, Città di Castello, which fell under the domination of Cesare Borgia, and Assisi, a city that returned under the rule of the Church under Pope Pius II.

One of the main effects of the union with the Church was a change in the administrative and fiscal regime, followed by a gradual transfer of the communal management from the bourgeois to a small, aristocratic group controlled by the papacy.

Between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the region was greatly affected by the transition to the papal system, which resulted in a tendency of the Umbrian economy to isolate and become self-sufficient compared to the other regions of Italy. This is one of the reasons why the region witnessed an industrial and commercial decline.

The crisis was equally profound in the agricultural field too. The reforms carried out during the sixteenth century yielded little results, and the absence of a strong maintenance policy caused the proliferation of swamps.

In this profound crisis of the social and economic structures, the phenomenon of brigandage broke out which, in spite of the repressions of Pope Clement VIII, succeeded to mix social aspirations and noble claims.

The eighteenth century found a desolated landscape in Umbria, characterized by a substantial immobility of all sectors. This stagnation was interrupted in the second half of the century with the arrival of the French troops in 1797. These changes, however, were welcomed with skepticism and even with hostility, not only in Umbria but in other territories of the Pontifical State as well.

During the Napoleonic period, Umbria was first divided into two departments, Trasimeno and Clitunno. In 1809 the region was united to the French Empire under the name of the department of Trasimeno, then it returned under the Pontifical State in 1814.

Despite the political changes, the region was rather distrustful of the revolutionary motions, although subsequently, the ideals of Risorgimento spread among the liberal and bourgeois sectors. The Second Independence War, in fact, saw hundreds of Umbrian volunteers join the Sardinian army.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Perugia started uprising, yet its attempt was quickly repressed by the papal troops. In 1860, under a short occupation by the Sardinian army which was marching towards the Bourbon kingdom, Umbria sought and obtained annexation to Italy as a result of a plebiscite.

The slow improvements during the decades after the unification mainly concerned the countryside, thanks to the formation of an agricultural bourgeoisie and to the improvement of the agricultural techniques. The beginning of the twentieth century ended with the First World War, an event that ensured the marginalization of “old” Umbria and the advent of a “new” region centered on industrial development.

During the fascism, Umbria became one of the major industrial areas of the country, but the Second World War caused a lot of damage to the region, above all in Foligno and Terni. In these areas, the steel industries were dismantled by the Germans, then ridden to the ground by the allied bombings.

Following the Second World War, the region underwent a period of reconstruction during which emerged new industrial plants, including a few hydroelectric plants on the rivers Tiber and Nero. Despite it, Umbria remained a mainly agricultural region that sets itself apart from all the others.

Archaeology in Umbria

Archaeology is well represented in Umbria, especially in Orvieto, the main Etruscan center of the Umbrian territory. In this area were found numerous archaic remains belonging to both the Bronze Age and to the Roman Republican era. The most famous is probably the statue of Arringatore, preserved at the Archaeological Museum of Florence.

The area to the west of Lake Trasimeno and Chiusi is rich in cinerary evidence, while the left bank of river Tiber is rich in testimonies of the Umbrian civilization, especially in the area of Foligno. The Etruscan centers of Civitella D’Arna, Bettona, and Todi are also rich in artifacts, such as city walls and necropolises. In these areas was also found a series of important bronze statues, which are exhibited at the Vatican Museums, including the statue of Mars.

The Roman monuments, especially those belonging to the imperial ages, are also noteworthy. The most important archaeological sites are Spello, Carsulae, and Otricoli. The first two are famous for their notable Roman portraits, while Otricoli was rich in statues and mosaics, with artifacts currently exhibited at the Vatican Museums.

Other significant monuments to mention are located in Assisi. The remains of a temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva is located here. Spoleto, Gubbio, Bevagna, and Norcia are other settlements rich in archaeological testimonies.

The presence of numerous infrastructure works, including the bridge of Augustus at Narni is another archaeological site worth noting. The residential and public building remains also tell the story of past civilizations. The most important are located at Carsulae and Assisi.

It is also important to mention the presence of numerous ceramic remains, among which the most spectacular are those belonging to the ceramic factories of Bevagna and Otricoli. These “jars of Populus” are made of unvarnished black ceramic decorated with Hellenistic motifs. The jars, dating from the first century BC, were also common in Lazio and Tuscany areas.

Travel Guides

[wudrelated include="1837"]

The Umbria Region of Italy

[wudrelated include="2714"]

Cities of Umbria

[wudrelated include="4237"]