Campania – History

From a historical point of view, Campania has two identities shaped by the peculiarities of its territory. Geographically speaking, the region is characterized by a low landscape on the coastal strip and the plain of Volturno, and mountainous areas in the provinces of Avellino and Benevento.

The coastal strip constitutes a unique territory, presenting itself as an intensely urbanized area interspersed by intensive agricultural works, industrial establishments, and resorts of global importance.

At the heart of this coastal region is Naples. The city was the capital of the largest Italian state and one of the major cities in Europe for a long time. Moreover, Naples has been the point of interchange between continental Southern Italy and the rest of the world for centuries.

After the development of communications and the implementation of the Adriatic axis, Bari started to threaten Naples’ position. In fact, not only Bari but also other Adriatic ports have reduced, over the time, the hegemonic role of Naples. Nevertheless, the city, despite its problems and structural gaps, succeeded in maintaining its appearance and pride of a great capital.

The Neapolitan conurbation, stretching between the volcanic areas of Vesuvius and Campi Flegrei and overlooking a gulf of rare beauty, is the center of the region not only geographically but also historically. In fact, this region has always represented an important interest for prehistoric civilizations, followed by the Greeks, Romans, and subsequent cultures.

The name of the region has its origins in the classical era, when it was used to designate the Tyrrhenian coast south of Lazio, and it fell into disuse in the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, the term remained alive in literary use and, after the unification of Italy in the 19th century, Campania took its name back for good.

Prehistory of Campania

The earliest artifacts in the region were found on the island of Capri, at a site dated to the Lower Paleolithic age and attributable to the middle-upper phase of the Acheulean Era. The influences of the various prehistoric cultures are also visible in the area of Marina di Camerota, more precisely in Cala d’Arconte, Capo Grosso, and Cala Bianca. Some remains referring to two distinct phases of the Aeolian cultures have been discovered in these areas.

Many coastal caves reveal remains of the Mousterian Phase, above all in the areas of Poggio and Taddeo. In fact, several teeth and a fragment of a femur bone belonging to a Neanderthal humanoid were discovered in Taddeo Cave. Other human remains, more precisely a fragment of a jaw belonging to a child about 3 years old, were found in the area of Mt. Molare.

The artifacts belonging to the Upper Paleolithic era are also numerous in the region. Some of the most noteworthy sites are the cave of Castelcivita located in the surroundings of Palinuro.

In Capri, the Grotta delle Felci housed remarkable ceramic objects belonging to the Neolithic age.

The Copper Age is represented in Campania by the Gaudo culture. Some important settlements from the Lower and Middle Bronze Age, such as Palma Campania and La Starza, show traces of a sudden end of cultural development due to a period of volcanic activity. Nevertheless, it is possible to document a rich stratigraphy containing materials from the Neolithic to the Late Bronze Age.

Of noteworthy importance are the remains of the buildings in Buccino, belonging to the Lower Bronze Age. These edifices and complexes are testimonies of a blossoming phase in the area. Another important archaeological site is the inhabited settlement on the island of Vivara where large amounts of Aegean ceramics were discovered.

Last but not least, we should also mention the cultural facets of the Apennine region. The remains belonging to the Age of Iron and are primarily funeral sites, including a series of incineration necropolises in Capua, Sala Consilina, and Pontecagnano. The remains show clear relations to the Villanovian culture.

History of Campania

Campania became one of the Greek colonies on the Italian Peninsula during the 9th century BC. In fact, some of the first Greek colonies in Italy were settled in the region. Cumae affirmed its domination on Vesuvius and on the coast between the 8th and 6th centuries BC. The foundations of Parthenope, the Greek settlement that would eventually become Naples, were also laid in this period.

Naples, previously called Neapolis, was founded in the 5th century BC shortly after the Cuman and Etruscan civilizations set the bases of Capua to fight for control over the merchant routes in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

In the same century, the region also witnessed the Samnite invasions, and this population ruled for a short period of time. In the 4th century BC, the Romans gained control of the region and settled one of their colonies here.

During the Roman domination, Campania saw a period of economic and social development that started with the construction of the Via Appia, which linked the southern regions of Italy to Rome.

From the end of the 2nd century BC, especially in the areas of Baia and Miseno, Campania transformed into a destination for the noble Roman families. In this period numerous residential complexes emerged, yet, after the Social War between 91 and 87 BC, Rome sent a colony of 50,000 legionnaires to Campania.

The Romanization of Campania was concluded by Augustus and, with the exception of a few cities, Campania entered into a period of slow decline. One of the few cities that strengthened in social status and economy during the Imperial Age was Pozzuoli, whose port remained the main base for the Roman expansion towards the East.

The Roman development in the region was suddenly interrupted in 79 AD by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The ashes and lava of the volcano erased the settlements of Herculaneum and Pompeii. Saved from the disaster, Naples remained an important center, but its political weight became nearly irrelevant.

Following the eruption of the volcano, Campania became a weak region subject to the barbarian invasions, and it was heavily involved in the Gothic War. In the early Middle Ages the territory was divided between the three ducats of Benevento, Salerno, and Capua, while the Byzantine Empire established three other ducats in Naples, Amalfi, and Gaeta. The religious power in the region was concentrated in the monastery of San Vincenzo al Volturno.

In the ninth century, the Normans moved the political and economic center of Southern Italy to Sicily, attributing administrative and control functions to the feudal aristocracy. The region became secondary for a long period of time until a new state was constituted in 1220 by the Swabians. By ordinances and conception, this was one of the most modern states of the time.

After Frederick II’s death in 1250, the region passed through a period of bloody struggles. In the battles of Benevento and Tagliacozzo, Manfredi and Corradino were defeated by Charles of Anjou who decided to move the capital from Palermo to Naples in 1282.

Under the Anjou dynasty, Campania saw a period of recovery, although the economic toll was rather high. Unfortunately, the Anjou decided to engage in a series of conflicts against the Aragon dynasty. These political struggles had devastating effects on the region’s economy, and Naples, in particular, became a shelter for a dense group of people belonging to the lower class, especially peasants.

This massive migration of the lower classes to Naples resulted in an exacerbation of the negative sanitary conditions of the dwellings, but also of the city as a whole.

Campania passed under the rule of the Kingdom of Aragon in the 15th century. In this period the region was subject to a profound administrative restructuring that included local barons. As a result, Naples became the most important political and economic center in Southern Italy.

In 1495, the descent of Charles VIII and the intervention of Ferdinand of Aragon made Campania the scene of continuous battles that ended in 1503 with the Spanish conquest of Naples. The Spanish kingdom entrusted the government to viceroys, and in the first half of the 16th century, through the actions of Pedro de Toledo, the Emperor Charles V implemented a policy of censorship aimed at the liquidation of the region’s autonomous remnants, whose fates were increasingly linked to Spain.

Naples consolidated its role as capital of Southern Italy right before the greatest crisis of political and administrative identity of the region. At the same time, the city also became a source of contradictions. Nevertheless, in the second half of the 16th century, the region enjoyed a period of economic improvement that ended in 1585 with the agrarian crisis.

The conjunction of the region’s economy with the agrarian crisis was dramatic. The shortcomings of the economic and administrative structure weakened the position of the region, and the situation worsened when the predatory tax policy implemented by Spain put new weight on Campania.

During the 17th century, this economic crisis caused many revolts, including the famous one by Masaniello that resulted in the abolishment of the viceroys. During this revolt, the economic and political situation strengthened the baronial power and, in the countryside, the revolt targeted the symbols of feudalism.

The feudal aristocracy was victorious; nevertheless, it showed its inability to control the territory shortly after the victory, and in the second half of the 17th century, a “civilian class,” favored by the policies of Madrid took the lead. This civilian class consisted of public officials, lawmakers, bourgeois, and intellectuals who assumed a significant political and administrative role.

After a short period passed under Austrian dominion, Campania returned to the Spaniards in 1734. At the same time, Charles III of Bourbon inaugurated a period of moderate reforms in Southern Italy. However, in 1759, the throne of Spain was given to the successor of Charles, Ferdinand I of Bourbon, who at the time was only eight years old.

In the same year a spread of pests had a negative impact on the agricultural production of the region, and without a proper leader, Campania entered into a new period of decline. Ferdinand I gained full powers over the throne in 1767, but he left the governance of Campania to this wife, Maria Carolina of Hapsburg-Lorraine.

Between 1759 and 1767, Bernardo Tanucci ruled over Campania and continued the reformist policy delineated by Charles III. This policy, based on the rebirth of the local power against barons and feudal nobility, together with intensive intellectual work, led to instability in the region. During this time, thanks to the numerous intellectuals, the first universities and Masonic lodges were developed in Campania, culminating with the short-lived Parthenopean Republic.

The profound divisions between bourgeois and the intellectual class on one hand, and between peasant farmers and the proletariat, on the other hand, favored political reactions and Ferdinand’s return to the throne.

In 1806, shortly after Napoleon conquered the Kingdom of Naples, Giuseppe Bonaparte was appointed King of the Two Sicilies, succeeded in 1808 by Gioacchino Murat. The main reform adopted by the French was the abolition of feudality, while other reforms helped to create a new urban class of officials, primarily constituted of nobles and bourgeois.

In the second half of the 19th century, Campania welcomed Garibaldi whose victory during the Battle of Volturno marked the end of the Bourbon dynasty.

After a short period of development favored by the export of agricultural products, in the last quarter of the 19th century, the region underwent another economic crisis, which resulted in massive emigration.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the misery of the hinterland was reflected in the development of the coastal area and especially of Naples which, with the establishment of the steel plant in Bagnoli, became the largest labor center in Southern Italy.

The impact of Fascism in the region was somewhat marginal. World War II mainly affected Campania from 1943 onward and it heavily involved the areas of Naples and Salerno. Reduced to a disastrous state by the war, Campania faced significant economic and social problems. In 1980, after a devastating earthquake struck the region following further economic struggles, the region saw the rise of organized crime.

In recent years, thanks to a wealth of cultural and historical sites, tourism has strengthened Campania’s economy.

Archaeology of Campania

Out of all the Italian regions, Campania is one of the richest in archaeological evidence that documents the various phases of development of its civilizations from prehistory to the successive colonization by the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans.

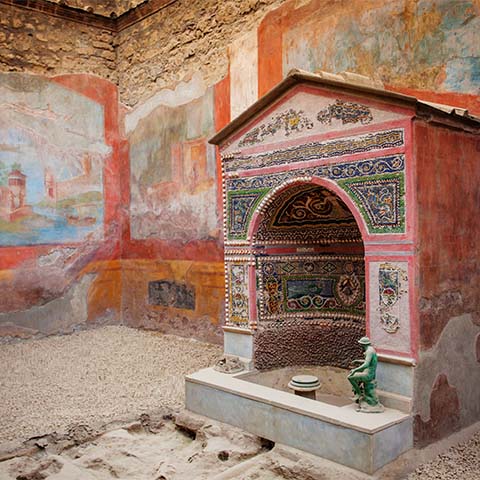

The passage of these people is attested in various centers, especially in those that were originally buried under the ashes of Mount Vesuvius.

Some of the best-preserved sites are Pompeii and Herculaneum. The remains of classical art are documented in many other centers as well. Among them, we can mention Paestum, Naples, Capua, Nola, Baia, and Stabia.

Moreover, numerous artifacts are exhibited in the many archaeological museums present throughout the region, and Naples is home to the largest archeological museum in Italy.

Travel Guides