Verona is one of the most famous cities in Italy and the capital of the homonymous province. The largest city in Veneto is best known as being home to Romeo and Juliet.

Shakespearian dramas apart, the city has developed uninterruptedly and progressively for over two thousand years; over the centuries, it developed outstanding artistic elements that now blend in a unique mixture of styles from different eras.

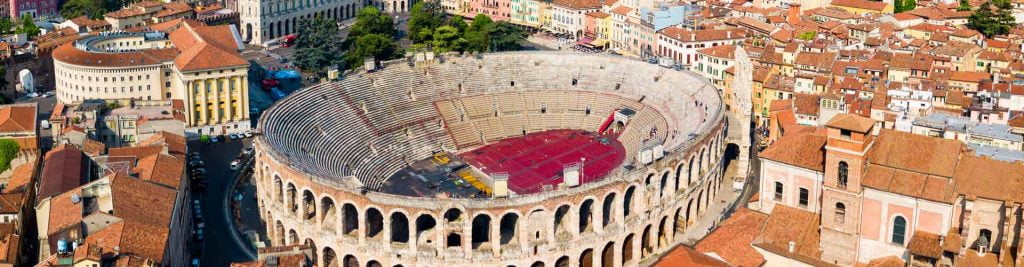

For its art, architecture, and urban structure, Verona has been declared an excellent example of a fortified city and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Although the origins of the name are unknown, historians believe it could derive from either Venetian or Gallic substantives. The most interesting theory, however, attributes the name to the Etruscans, mainly because there is a second Verona located near Lamporecchio, in Tuscany.

According to the legend, the mythical founder of the city was the Gallic chief Brenno who settled in the area and established Vae Roma, roughly translated to cursed Rome; a name that eventually turned into Verona.

PREHISTORY OF VERONA

Based on archaeological evidence, it is safe to affirm that the area of Verona has been inhabited since the Neolithic age.

It is believed that the first settlement was a village near the southern area of the Hill of St. Peter, along the Adige river. This area contains multiple finds and artifacts including remains of ancient dwellings.

During the protohistoric period, the area became home to the Gallic Cenomani tribe who settled in the west, up to the course of the Adige, as well as on the hilltop. Evidence suggests that these tribes coexisted alongside the Venetians.

However, the Latin historians make it hard to identify the actual origins of the city, which are attributed to the Etruscans, Venetians, but also the Reti and Euganei civilizations.

Ancient Roman historians confirm the Venetian ethnicity of Verona’s population in the second century BC. Their presence is also well documented in the area of the Hill of St. Peter. Nevertheless, other Roman historians, including Pliny the Elder, formulated the hypothesis of different origins.

The first contacts between Rome and Verona are documented around the third century BC. The two cities formed an alliance almost immediately, perhaps during the incursions of Brenno in Rome.

In 174 BC, following the subjugation of the Cisalpine Gauls and the beginning of the colonization of the Po Valley, Verona started to reveal its great strategic importance.

Thanks to Caesar, it obtained Roman Citizenship in 49 BC, then it was granted the status of municipium, an event that marked the beginning of the Res Publica Veronensium.

During the Republican period, Verona developed its economy and relations, and the city began to grow and modernize its infrastructure.

In the imperial period, it became an even more important strategic node, and was temporarily used as a base for the legions.

Under Emperor Vespasian, Verona reached the pinnacle of wealth and splendor, including the magnificent Arena that survived and can still be seen to this day. In the meantime, the population of the city grew and managed to exceed 25,000 inhabitants.

With the beginning of the barbarian invasions, the Roman Emperor Gallienus decreed the expansion of the city walls in 265 AD and succeeded to fortify the city in just seven months.

HISTORY OF VERONA

Verona thrived under the Romans, but with the fall of the Empire, it suffered barbarian invasions before passing to Theodoric the Great. Under Germanic rule, it became a military center of primary importance and the favorite seat of the king.

Theodoric restored the former glory of the city and rebuilt the walls destroyed during the previous barbarian incursions.

Subsequently, the city passed to the Lombards, who put an end to the brief Byzantine dominion, which was restored after the defeat of the Ostrogoths during the Gothic War. Verona became the capital of the Longobardi court until 571 when the seat was moved to Pavia.

However, Verona still remained the capital of a Lombard duchy and one of the most important cities of Longobardia Maior alongside Milan, Pavia, and Cividale.

On May 15, 589, the marriage between Autari, the King of the Lombards, and Theodolinda, the daughter of the Duke of the Bavarians, was celebrated in Verona.

The dominion of the Lombards over Verona lasted for almost two centuries, until the birth of the Carolingian Empire. However, the city’s privileged position did not end under the new rulers, with Verona becoming one of the preferred destinations of the new emperors.

During the eleventh century, while the rest of Northern Italy was devastated by numerous wars, Verona remained faithful to the Holy Roman Empire and helped it during the long struggles for investitures of the Papacy.

The birth of the Commune of Verona happened naturally in 1136, with the election of the first consuls. From those times, however, there started to be a notable discrepancy between the two factions that would later call themselves the Guelph and the Ghibellines.

Verona was particularly struck by the struggles between these two parties, mainly because the main forces of the Guelphs were located in the countryside, with the support of the powerful House of Sambonifacio. While the city was predominantly Ghibelline – among the greatest exponents of the era we can mention are the Montagues, a family made famous by Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Faithful to the Church, Verona became a papal seat for five years, and Pope Lucius III established the Papal Curia of Verona in 1181.

In a Conclave held in Verona in 1185, the Catholic Church elected Pope Urban III, a cleric determined to excommunicate Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. But the Veronese, fearing retaliation, protested against it to such an extent that the Pope decided to move the Papal Curia to Ferrara.

The disputes between the opposing factions came to an end in 1223, when Ezzelino III da Romano obtained power over Verona. At first, Ezzelino’s regency was peaceful, but after persistant rumors of a Guelph attack, he imprisoned most Guelph exponents of the city while assigning himself the title of the imperial vicar.

That moment marked the beginning of fierce battles between the city and the Guelph castles. These events drew the attention of Frederick II, the emperor who granted Ezzelino the vicariate.

But despite the emperor’s worries, Ezzelino continued with his territorial expansion until Pope Alexander IV managed to capture the vicar.

At Ezzelino’s death, Verona became the only city under his rule that did not become a victim of the Guelphs.

In fact, the Ghibelline faction retained its power in Verona, and, with Mastino I della Scala, the city seamlessly transformed into a Signoria.

Under the della Scala, the city rediscovered a new period of splendor and such importance that Dante dedicated an entire sonnet to it in the Divine Comedy.

At the same time, Verona spread its power over Northern Italy; della Scala became lord of Verona, Padua, Vicenza, Montagnana, Bassano, Treviso, as well as the imperial vicar of Mantua and the head of the Ghibelline faction in Italy.

Having occupied almost the entire mainland of the Veneto region, the lordship of the famous Scaligeri family became very worried about Venice.

However, the expansionist policy of Verona was interrupted by the sudden death of Cangrande della Scala merely a few days after the conquest of Treviso, officially because of congestion, but more likely due to poison.

The unexpected death of Cangrande left the lordship without direct descendants; therefore, power was assigned to his nephew, Mastino I della Scala who, with the acquisition of Lucca, expanded the lordship up to the Tyrrhenian Sea.

This territorial expansion started to frighten the neighboring states who established the formation of a league promoted by the Republic of Venice.

The league gathered the most powerful families of the region including the Gonzaga, Visconti, Estensi, and Carraresi, who joined forces in a fight against Verona.

Finally, the city was occupied by the Visconti who implemented a short but rigid dominion.

Taking advantage of the death of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Francesco II da Carrara, backed by the exiled Scaligeri including Guglielmo della Scala, entered the city.

While della Scala died under mysterious circumstances a few days later, Francesco II da Carrara proclaimed himself Lord of Verona on May 24, 1404.

The citizens did not enjoy this change, and Venice, taking advantage of the discontented people and of the disturbances that were causing struggles in the city, managed to enter Verona and remove the brief dominion of the Carrara.

Indeed, on June 24, 1405, Verona declared its dedication to Venice. Under the Venetian Republic, the city enjoyed a long period of peace that lasted for the rest of the century, until the Republic was attacked by the powers of the League of Cambrai.

At the end of the war with the Holy Alliance, Verona entered a new period of prosperity that ended in 1630 due to the plague brought into the region by the German soldiers.

The disease represented a real disaster for the city, and half of the population died. After the plague, Verona entered into a period of slow recovery that lasted for almost two centuries.

Nevertheless, the sixteenth century saw a revival of the economy and the construction of churches and other important buildings.

The artistic and cultural rebirth included the development of the famous Veronese concerts. In the same period many academies that enriched the cultural activities in the city were founded.

In 1796, during the Italian Campaigns, the Austrians were defeated in Piedmont by Napoleon, causing them to retreat to Trentino. At the same time, Napoleon and French revolutionaries violated Venetian neutrality, occupied Peschiera, and subsequently entered Verona.

During the French occupancy, the city lost many of its artworks that were transported to the Louvre and other museums in Paris.

With the Treaty of Campo Formio, Napoleon ceded the city to the Austrians, and subsequently, Verona was divided into a French and an Austrian side, remaining under the respective occupancies until the beginning of the nineteenth century, when it was fully occupied by the French.

Following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Verona permanently passed into Austrian hands, becoming the most important city of the Hapsburg strategy against Piedmont’s attacks.

In the 1860s, following the history of all Italian regions, Verona became part of the new Kingdom of Italy. With the conquest of Veneto by the Savoy, the city entered a period of relative tranquility that was only disturbed by an economic crisis that lasted until after World War II.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Verona was subject to a flood event that pushed the municipality to build the so-called embankments.

During World War II, Verona was profoundly affected by bombing during which most of its buildings were destroyed or badly damaged.

In the postwar era, Verona focused on the development of its culture and service sectors. Today, the city is an important university center and one of the most artistic cities in Italy.

ARCHAEOLOGY OF VERONA

Archeological evidence in Verona and its province is abundant, and most structures that survived over the centuries date back to the Roman era.

Undoubtedly, one of the most important sites is the Roman amphitheater, now known as the Arena of Verona. Used for the same purpose from antiquity to these days, this is one of the few Roman amphitheaters that enjoyed uninterrupted activity since it was built.

Near Verona, the Pantheon of Santa Maria in Stelle is another noteworthy site. This hypogeum supposedly served as an aqueduct built in the late Imperial Age and developed until the Middle Ages.

The province is also scattered with evidence from the pre-Roman era, including Mesolithic and Lower Paleolithic artifacts.

The Roman Theatre, not to be confused with the amphitheater above, is another important Roman remain. This place, still sporadically used for shows and other cultural activities, houses the Civic Archaeological Museum.

Travel Guides

The Veneto Region of Italy

The Cities of Veneto, Italy