Reggio Emilia is one of the main cities in the Emilia-Romagna region, located in the Emilian plain on the right bank of the Crostolo stream. An important settlement along Via Emilia, the city still preserves important traces of the Roman urban core.

The settlement extended considerably in the Middle Ages and received its city walls in the thirteenth century. In the fourteenth century, the city reinforced its city walls only to have them demolished in the upcoming centuries with the expansion of the territory.

A bishopric and university seat, Reggio Emilia is a city rich in history that holds close links with its past.

PREHISTORY IN REGGIO EMILIA

Traces of the first human settlements in the territory date back to the Paleolithic era. The first civilizations to settle in the territory were perhaps the Etruscans, followed by the Celtic tribes. However, the origins of the city are debated.

It is believed that the name of the city has Ligurian origins, while others believe the origins are actually Celtic.

Despite this, what is certain is that both names correspond to the Latin forum, and recent archaeological discoveries testify the existence of a prolific urban center dating back to the Bronze Age.

The first Roman settlers began arriving in the area in 193 BC during the final conquest of the region. During these years important consular roads were built, while the primitive nucleus of the city started to develop.

In this period, Reggio Emilia was only a modest Roman castrum that served as a transition point for the Roman troops who were moving towards the north. But thanks to a strategic geographical position, Reggio Emilia subsequently developed into a flourishing settlement and became an effective Roman colony ideated to control the surrounding territory.

At the same time, the settlement also became an important transit and trade node along Via Emilia.

As a Roman settlement, Reggio Emilia gained important temples and civic buildings whose remains are still visible in numerous sites scattered throughout the city. According to the remains, it is believed that Roman Reggio Emilia occupied the perimeter between the current Campo Samarotto and San Girolamo up to Guido da Castello, Campo Marzio and Via Dante Alighieri.

HISTORY OF REGGIO EMILIA

Due to its strategic position, the city became a lively center with a host of professional guilds, including blacksmiths, dyers, wool carders, and cloth weavers. The Roman city experienced its period of maximum prosperity in the Imperial era, during the first and second centuries AD.

Shortly afterward, the settlement entered into a presumable decadence. In 227, the first wave of barbarian populations struck the region, destroying several of its thriving urban centers. Later, a tribe of Slavic origins established itself between Parma, Reggio Emilia, and Modena.

Between one invasion and another, pestilence depopulated the city, destroying its guilds and agricultural income.

In 387, Ambrose, Bishop of Milan and future saint, described the situation in Reggio Emilia in one of his letters to the Christian community of the region as unimaginable. The uncultivated fields and lack of population gave a desolate feel to the settlement.

At the same time, the region started to experience the spread of Christianity. Archaeological evidence of the new religion in the area dates back to the middle of the fifth century, and the first mention of a bishop in the area dates from 451.

Among the clergy, Prospero stood out as the most illustrious, becoming the patron saint of the city, although it is unclear how he became a bishop.

Yet, it is certain that the figure of the bishop, heir to some of the prerogatives of the Roman magistrates, was assuming a central role in the city in a moment of great uncertainty for military and civilian life. Without city walls or any defensive structure whatsoever, Reggio Emilia was subject to invasions from various barbarian tribes.

The city did not construct any defensive structures until the tenth century, when one of the bishops, Peter, obtained formal concession from the Emperor to build a castle and a mighty city wall as defensive structures. Yet, these defensive structures were only built after the city had been devastated by the troops of Alaric, Odoacer, and Theodoric, not to mention the Byzantines in 526.

However, the power of Justinian had a short life, and in 568 the Longobards won supremacy over the city.

The Longobards reduced Reggio Emilia to a negligible settlement that would have assumed the pre-eminent functions of a fortified center that was witnessing an almost irreversible decadence. There are a few testimonies from this period, although it is believed that a Longobard church dedicated to St. Michael was built near the current Cathedral.

The fall of the Franks in 773 brought war in the peninsula, and Reggio Emilia found itself involved in the events. Charlemagne occupied the city and established the Reggio Committee here, whose boundaries coincided with those of the diocese.

Some of the oldest documents of the city date back to this period, attesting to the concession of Reggio by the King of the Franks to the church in 781.

The feudal system implemented by the Carolingians began to add unity and balance to civil life after centuries of confusion, but the last foreign invasion that struck the city in 889 brought further destruction. In fact, from 889, the Hungarian invasions systematically devastated the population in many centers along Via Emilia.

In this period, the city lost its Monastery of St. Thomas and the primitive Church of St. Prospero located outside the city walls. At the same time, Bishop Azzo was killed.

What resulted was a period of insecurity which made people escape from the plains towards the hills in search of safer shelter. This gave rise to the castles belonging to the Middle Ages.

In the city, Peter, the successor of Azzo, also started to build a robust defense system. Although small, the castle of the bishop contained a cathedral dedicated to Santa Maria, while in 997 the construction of the new church dedicated to San Prospero was completed.

While the episcopal power received important sanctions in the city, the emperor Otto I granted comitial authority to the Bishop Ermenaldo. In 1027, Corrado II nominated another prelate chosen by the imperial power and that served the purposes of Canossa, whose domains eventually extended from Mantua to Tuscany.

Upon the death of Countess Matilda, whose role was decisive for the political destiny of Europe, the first form of an autonomous municipality with a government that focused on the welfare of the citizens in Reggio Emilia was affirmed.

The first news about the existence of the municipal magistracy dates back to 1130. At the time, the city had two consuls whose role was to support the authority of the bishop. Due to a political and civic revival, the feudal nobility left their countryside castles and began to occupy the urban center.

This movement created the ideal base for conflicts, which characterized the city life in the upcoming years.

But at the same time, the municipality was also extending its authority over the surrounding area, sending its delegates to the stipulation of the peace treaties, primarily the treaty signed in 1183 in Constance. Six years later, the bishop swore allegiance to the municipality on behalf of all men subject to his jurisdiction.

The beginning of the thirteenth century found Reggio Emilia divided between the civil wars of the nobles against the commoners.

These wars were only the prelude to the continuous battles between the Guelph and the Ghibelline factions.

In 1290, the city, worn down by internal clashes and conflicts with neighboring cities, passed under the rule of the Este.

This marked the beginning of the Este domination in the region, although two other families, the Fogliani and the Gonzaga, were also struggling for supremacy. During this time, the Lords of Mantua gained control over Reggio Emilia, contributing to a decisive change to the urban layout conducted at the end of the twelfth century.

During the last part of the century, the Gonzaga Family managed to establish themselves in the region; in the middle of all these struggles, Reggio Emilia was also fighting the epidemics of the century and surviving the continuous conspiracies of the nobles.

In 1371, the House of Gonzaga sold the city to the House of Visconti, who ruled the area until the beginning of the next century.

The fifteenth century opened with the dominion of the Terzi, but in 1409 Reggio Emelia returned, this time definitively, under the orbit of the Este who ruled the city. Although there were brief interruptions, until the Unification of Italy.

With the return of the Este, a period of peace and slow recovery began, although the city was alternating governors and administrators. Yet, some of these governors who brought culture and arts into the city were illustrious.

One of them was Matteo Boiardo who became famous for his literary merits. Francesco Guicciardini governed the city from 1517 to 1523 during the brief period of papal domination and until the return of Alfonso d’Este. At the same time, the city was living the Renaissance thanks to the consolidation of favorable economic conditions.

The beginning of the sixteenth century found Reggio Emilia ruled by Lucrezia Borgia, the Duchess of Ferrara, Modena, and Reggio. Borgia sponsored the introduction of new arts and crafts into the city, providing strong enrichment opportunities for the working classes.

But this golden age only lasted for roughly a century. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the city was characterized once again by serious economic crisis and the plague. Reggio Emilia, the second city of an almost unworthy duchy, began to alternate decadence with periods of recovery, characterized by the growth of discontent among the population and municipal resentment.

To complicate things further, the city suffered a memorable siege in the Spaniard attempt to conquer the region in 1655. What followed was a series of wars, changes of alliances and oscillations between prosperity and decay.

With the death of Alfonso d’Este, the city passed under the rule of Laura Martinozzi, Alfonso’s widow. Under her rule, Reggio Emilia witnessed another period of relative tranquility that saw a slow increase in the population along with cultural enrichment.

The first half of the eighteenth century took its toll on the city. The European wars of succession were characterized by territorial clashes, sieges, attacks, and misery, while the ducal authority was poorly felt. Reggio Emilia then entered another period of peace until the advent of Napoleon.

But nothing served to revive the fate of the city, and the end of the century found Reggio Emilia struggling with the echoes of the French Revolution. Despite the Duke’s attempts to restore peace, the first signs of rebellion were already emerging in 1791, when under the pretext of an unhappy society, the people rose for the first time in riots.

This was only the prefiguration of what would have followed during the arrival of the French in the early months of 1796. After the Duke fled, the noble democrats of Reggio Emilia started to exert pressure to obtain privileges, including the establishment of an administrative autonomy encouraged by Napoleon.

The middle of the year brought nothing but new tensions, which saw Reggio Emilia degrading in the struggles for supremacy. On the night between the 25th and 26th of August in the same year, the locals raised their tree of liberty in the main square, including the signs of the Republic of Reggio Emilia.

Later that year, with the opening of the Jewish settlements and the struggles with the Austrians, the city completed its transition to a complete and sovereign institutional structure. But this period of autonomy had a very short life, and Reggio Emilia joined unified Italy together with the other cities in the region.

Today, Reggio Emilia is known for its local culinary and wine products and a rich history that attracts travelers from all over the world.

ARCHEOLOGY IN REGGIO EMILIA

One of the most noteworthy places in Reggio Emilia from an archaeological point of view is the Civic Museum. The archaeological collections document the prehistory in the area; at the same time, a chronological itinerary takes visitors from antiquity to present day.

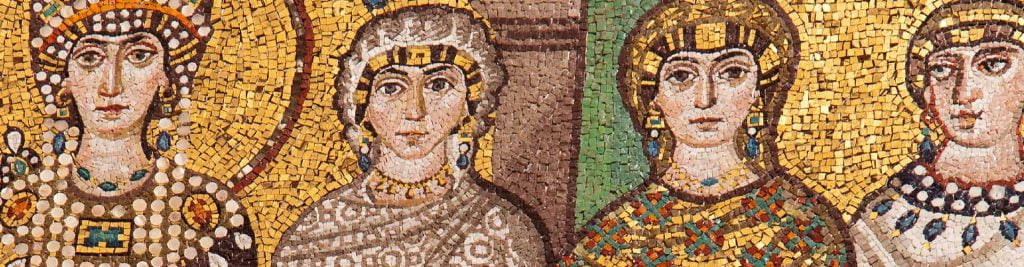

Besides prehistoric artifacts, the museum also houses a collection of Roman and medieval mosaics, a collection of epigraphs, architectural fragments, and sculptures from the Roman era to the modern age. The ancient artifacts belong to the Paleolithic era, while numerous Roman artifacts are also exhibited in permanent collections.

Besides the museum, the suburban villa of Mauritian is another interesting place to visit that includes a Roman necropolis and numerous funerary monuments. Moreover, numerous other vestiges are scattered in many places throughout the city.

Travel Guides

The Emilia Romagna Region of Italy

The Cities of Emilia Romagna, Italy