Pisa is a renowned Italian city and the capital of the homonymous province in Tuscany. Widely known for the Leaning Tower, the city attracts thousands of visitors each year and impresses with a long and rich history.

According to legend, the city was founded by Greek refugees who escaped from a homonymous settlement that was destroyed in the sixth century BC. It is said that these peoples reached the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea accidentally, giving life to the new settlement.

Whether this is true or not, what is certain is that this settlement grew into one of the most powerful Italic Maritime Republics alongside Genoa, Venice, and Amalfi.

Today, the city is home to three of the most important universities in Europe as well as the headquarters of the National Research Council, while proudly displaying its ancient legacy.

PREHISTORY OF PISA

Pisa emerged near the confluence of the rivers Arno and Serchio, in an area originally covered by a lagoon.

Despite the legends promoting a Greek origin, Pisa was, in fact, established by the Etruscans. It is believed the first civilizations settled here in the Villanovan period.

Since its birth, Pisa established itself as a maritime city dedicated to trading with the Greeks, Phoenicians, and even the Gauls from the mid-sixth century BC. Due to the strategic position and strong commercial relations, the Romans quickly became interested in this land. The Baths of Nero are one of the most important pieces of evidence of Roman Pisa.

A powerful maritime municipium despite its rather inland position, Pisa was the base of numerous enterprises against the Carthaginians, Gauls, and Ligurians.

In 180 BC, Pisa became a Roman colony granted with great autonomy under the consulate of Julius Caesar.

HISTORY OF PISA

Pisa did not suffer the decay of other Roman cities after the fall of the Roman Empire thanks to the complexity of the river system, which allowed for easy defense.

The environment constituted by the water basin and the nearby mountain defined a geographical arrangement particularly favorable to the defensive needs of the time. Furthermore, Pisa also enjoyed the presence of an important fleet.

Military strength helped the city establish itself as a principal port on the Tyrrhenian Sea and the trade center between Tuscia, Corsica, Sardinia, and the southern coasts of Spain and France.

With the victory of Charlemagne and the advent of the Franks, Pisa entered into a darker period from which it recovered quickly. Under the new administration, it was included in the Duchy of Lucca.

Otto I transformed Pisa into the capital of the duchy in 930. From a naval point of view, the emergence of the Saracens led Pisa to set up an autonomous fleet to fight against the pirates.

This was an important step for Pisa, as these fleets would subsequently guarantee the expansion of the city.

The first phase of Pisa’s power development saw the city engaged in battles against the Saracen pirates. These long naval enterprises lasted for about a century. In 1005 AD, Pisa liberated Reggio Calabria from the Saracen presence, while other anti-Arab expeditions were carried out by the noble Orlandi family who engaged in the conquest and occupation of Annaba, Algeria.

During these clashes, Pisa strengthened its power and position, serving many imperial and papal purposes.

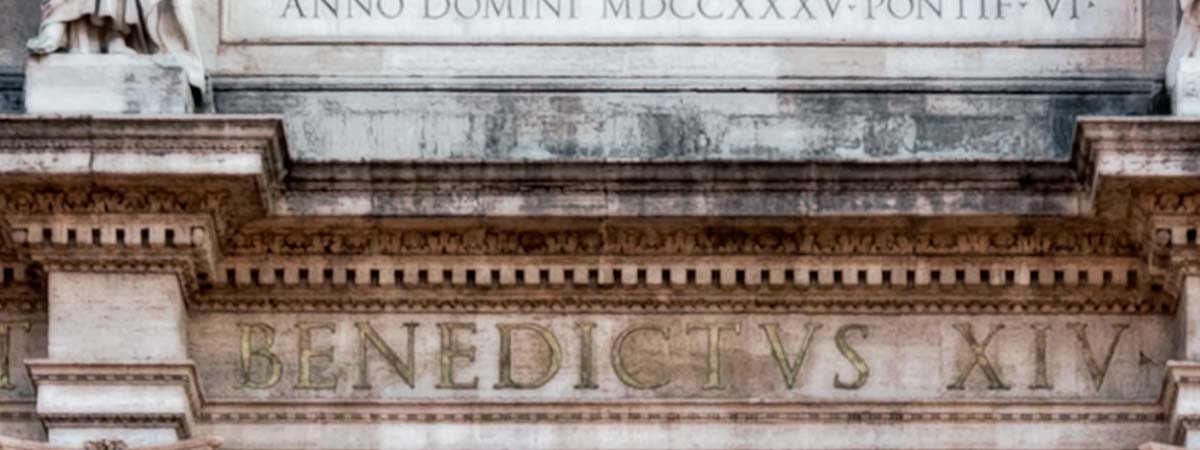

In 1092, Pope Urban II gave Pisa the rank of archiepiscopal center, while Henry IV granted it the right to elect its own consuls.

This last concession reflected a de facto situation since a strong institutional crisis had just ended with an agreement between the archbishop and the viscount, excluding the marquis.

Following this crisis, Pisa found itself allied with the nascent Norman power of the Kingdom of Sicily.

These concessions contributed to the enlargement of the economic and political power of Pisa. The city acquired possessions and commercial rights in the east of the Mediterranean, and less than two months after the first crusade, it sent a fleet of 120 ships to the Holy Land, providing supplies to the crusaders.

But the purpose of Pisa was not just that of providing supplies; indeed, the city’s intention was to establish colonies in foreign territories. During these expeditions, Pisa helped stabilize commercial colonies and found colonies in in Jaffa, Laodicea, Tripoli (Lebanon), and more.

Colonies were also founded in Jerusalem and Caesarea, as well as in Cairo, Constantinople, and Alexandria.

However, Pisa did not establish itself as a conqueror of these cities. In fact, all these cities granted Pisa with privileges and tax exemptions under the obligation to help with the defense in case of external attacks.

During the following century, the importance of Pisa in the Byzantine Empire grew even more. Indeed, the relations with the Empire improved to such an extent that Pisa was granted a preferred position, shadowing Venice.

At the same time, through the acquisition of the local church, Pisa also expanded in Tuscany, giving rise to a rivalry with Lucca.

But the rivalry with Lucca was not Pisa’s only concern. Concentrating its efforts on the construction of new ports and on attainment of new diplomatic and economic relations, Pisa started to acquire power by simply guaranteeing more advantageous treaties or monopolies to rival cities. This led to a rivalry with all maritime republics, but particularly with Genoa.

After the concession of primacy over Sardinia, the hostilities between Pisa and Genoa turned into war due to the contrast between mutual interests throughout the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Indeed, the Tuscan city intertwined profitable commercial relations with Savona and Montpellier, while Genoa formed partnerships with Antibes, Marseille, and Hyeres.

The conflicts between the two republics began in 1119, when Genoa attacked galleys belonging to Pisa, and lasted until 1133.

However, due to the Saracen attacks, the two republics did not engage in crucial wars against each other.

Towards the end of the century, Frederick I granted Pisa with the freedom to trade in the territories of the Norman Empire and the Kingdom of Sicily.

This edict had two consequences. On the one hand, it drew the resentment of Lucca, Florence, Massa and Volterra, who aspired independent access to the sea. On the other hand, it contributed to the outbreak of a new war with Genoa.

The object of the dispute with the Ligurian city was the threatening of Genoa’s position in Corsica and Sardinia, as well as the hoarding of the markets of Southern France, where Genoa enjoyed a clearly predominant position.

The hostilities began in 1165 with a failed attack of Genoa against Pisa and continued for ten years without striking episodes.

Another front of contrast between Pisa and Genoa was Sicily. Both cities enjoyed privileges on the island, a situation that led to various clashes that concluded with the conquest of Messina by Pisa, while Syracuse fell under Genoa.

Nevertheless, Pisa lost its commercial position in Sicily due to an agreement between the Tuscan Guelph League, led by Florence, and Pope Innocent III.

Later on, the Pope turned towards Genoa, weakening Pisa’s position even more, especially in southern Italy.

In the following years, the premises were laid for further subsequent clashes; despite the dark period, Pisa succeeded in intensifying its commercial relations with Southern France, including commercial agreements with Hyeres.

At the same time, the Republic of Pisa also started its expansion towards Spain, renewing its privileges with the Count of Barcelona.

Alongside these expansionist ambitions, Pisa was also attempting to penetrate the Adriatic and challenge Venetian supremacy. However, the Republic used a pacifist approach.

Indeed, Pisa stipulated a non-aggression agreement with Venice; nonetheless, the fall of the Byzantine Empire changed the balance and Pisa engaged in various actions against Venetian convoys.

Moreover, the desire to stifle Venice’s supremacy in the Adriatic concluded with numerous commercial and diplomatic agreements with various cities, including Ancona, Brindisi, and Zara.

Despite signing a ten-year peace agreement though, Pisa breached the clauses and attacked the Venetians. While it lost the battle, the situation did not lead to real war and at the beginning of the thirteenth century, the two cities stipulated a new treaty in which Pisa renounced its expansionist aims in the Adriatic while maintaining control over the territories it had already acquired.

The treaty was mostly established due to the anti-Genoese views of both Venice and Pisa, but the relation between the two republics was more of a collaboration than an alliance. From a cultural standpoint, Pisa also established its first university.

At the same time, despite the treaty with Venice, the city also began to normalize its relations with Genoa. The second decade of the thirteenth century saw Pisa and Genoa attending peace conferences that concluded positively, with the signing of treaties that guaranteed a twenty-year period of peace between the two maritime powers.

However, while closing treaties and armistices with the maritime republics, Pisa entered in conflicts with its neighbors, including Lucca and Florence.

Furthermore, the indissoluble link with the Empire also sharpened the tensions with the papacy.

On this tensioned background, a simple twist of fate saw Pisa becoming a rival of both Genoa and Venice, two powers that allied against those trying to disobey Pope Gregory IX.

Backed by the two powers, the Pope proceeded to excommunicate Frederick II and called for an anti-imperial council to be held in Rome.

But Pisa did not just sit and wait. After having tried in vain to attack Genoa by land, a fleet from Pisa joined the imperial fleet of the Kingdom of Sicily, defeating Genoa and capturing 25 galleys, thousands of prisoners, as well as two cardinals and various bishops.

This marked the beginning of the expansion of Pisa in the Mediterranean and the consolidation of the merchant classes, an event that changed the institutional structure of the city. Indeed, Pisa abolished the consuls, while the merchant classes and civilians gave rise to the “Capitano del popolo” or Captain of the People.

This change led to internal conflicts between families, above all between Della Gherardesca and Visconti.

After several attempts of pacification, a revolt led to the implementation of a new institution, the Anziani del Popolo, elected as representatives of the municipality.

The nobles, on the other hand, formed the legislative councils with the purpose to rectify the laws approved by the Major General Council and the Senate.

Developing unique economic strategies compared to Florence and Genoa, Pisa became a true power despite sporadic defeats.

Towards the end of the thirteenth century, the administration of the city was assigned to Guido da Montefeltro who assumed the position of Captain of the People, Captain of the City Militia, and Podestà.

From now on and throughout the fourteenth century, Pisa knew a period of freedom, communal respect towards the institutions, and large commercial expansion.

It closed treaties with the surrounding cities, including Genoa, Florence, and Siena.

However, the city was soon divided into two factions, the Bergolini, favorable to an opening towards Florence, and the Raspanti, part of the Della Rocca family and who opposed the approach towards the Guelph city.

The Raspanti succeeded in claiming control, naming Giovanni dell’Agnello as administrator. A friend of the Doge of Genoa, dell’Agnello instituted a period of great collaboration between the two cities, as evidenced by numerous merchants from Pisa opening activities in Liguria.

However, various struggles led the city to fall under the government of the Florentine Republic.

The initial period under the new rulers was harsh, both because of resentment and because of the competition existing between the merchants of the two cities. Moreover, those citizens considered dangerous by Florence were forced to leave Pisa.

As a consequence, Pisa entered a period of drastic impoverishment, as other families decided to follow the former leaders and leave the city as well.

What followed were years of heavy taxation alongside struggles between Florence and Lucca for the control over the former territories of Pisa.

The following centuries are characterized by numerous struggles between Pisa and Florence, with brief changes of fate.

During the Napoleonic occupation, many of the works of art in Pisa were stolen or moved to the Louvre museum.

Following the annexation to Italy, the history of the city coincides with that of the entire Italian state.

During World War I, the outskirts of Pisa served as a base to the Red Cross camp; situated rather far from the battlefront, the city suffered little damage.

Things took a different turn during World War II when the city suffered heavy bombardments during which many of its buildings were affected or razed to the ground.

In the postwar period, Pisa established itself as a powerful university center. The city is also an important tourism hub as well as an economic pole in Tuscany. Today, travelers from all over the world make the journey to Pisa to admire the Leaning Tower as well as the city’s countless other historic sites and monuments.

ARCHAEOLOGY IN PISA

With its rich history, Pisa has a host of interesting archaeological sites. The Baths of Nero feature Roman remains located in the heart of the city.

The pre-Roman origins of the city are confirmed by the Etruscan mound, while other prehistoric and Roman era remains are also scattered throughout the city.

An important artifact collection is also housed in the National Museum of Saint Mathew, as well as in the Museum of Art and Culture.

Travel Guides

[wudrelated include="1837"]

The Tuscany Region of Italy

[wudrelated include="1839"]

The Cities of Tuscany, Italy

[wudrelated include="4236"]