Parma is a renowned Italian city located in the Po Valley at the intersection of Via Emilia, with the Parma stream running through the town dividing it into two parts.

The primitive urban nucleus arose during Roman times, although the area has been inhabited since the Lower Paleolithic. This Roman settlement was located on the right bank of the river and was characterized by an orthogonal plan that is still visible in today’s Piazza Garibaldi.

From this original center, the city expanded towards the east of the stream and developed, between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries, the characteristic concentric lines of the medieval city.

In 1211, Parma began its expansion towards the west and incorporated the so-called Oltretorrente. Subsequent development triggered the construction of a new city wall that was demolished in the nineteenth century. Yet, the ancient layouts are still traced by the current circular avenues.

The Farnese and Bourbon families carried out vast renovation works inside the bastions, and the expansion involved the areas of Oltretorrente along the Via Emilia.

Today, Parma is a bishopric and university seat and a lively city that impresses with its culture and culinary traditions.

PREHISTORY OF PARMA

The origins of Parma are extremely old, and the first evidence of man’s presence in the area dates back to the Lower Paleolithic.

The artifacts were found in the hills of Traversetolo and in the basin of the Taro River. The area also holds important evidence of Terramare settlements belonging to the Bronze Age.

The first settlement located in the same area where the modern city would develop had Etruscan origins, and according to some studies, the current name of the city derives from the name of an Etruscan tribe called Parmni, or potentially from the Etruscan word meaning “circular shield.”

The Romans arrived in the area in 183 BC and transformed the name of the settlement to Parmae. Under Roman rule, Parma became an important reference point for all the surrounding plains. The construction of Via Emilia promoted a profound and rapid development of agriculture and breeding in the territory, but Roman Parmae served more as a settlement for the numerous families who relocated along Via Emilia.

Like many Roman settlements, Parma flourished under the rule of the Capital. Consul Marco Emilio Lepido transformed the settlement into an illustrious colony with privileged rights. The city received valid defensive works and soon gave rise to the so-called Road of One Hundred Miles, which linked Parma to Lunigiana, between Liguria and Tuscany.

This period was characterized by a flourishing commerce, thanks to the strategic position of the settlement at the intersection between the north and the center of the peninsula.

HISTORY OF PARMA

At the fall of the Roman Empire, the Goths conquered a territory already devastated by the wars of the last Roman Emperors and Attila, the fierce and powerful ruler of the Huns.

With the arrival of the Byzantines in the sixth century AD, the city regained its economic stability, which earned the settlement the nickname of the City of Gold. Parma became the seat of the military treasury, but the wars that characterized the period of the barbarian invasions impacted the city for centuries to come, bringing desolation.

In 569, Parma was conquered by the Longobards who rose the small Byzantine center to the rank of a Duchy governed by a Duke, with military and political powers. During this period, a new system of communication began to override the Roman order, and Parma’s segment of Via Francigena, an ancient pilgrim route linking the British city of Canterbury to Rome, was born.

This drew wealth to the region, and Parma witnessed the edification of numerous castles and inns intended to ensure that pilgrims and travelers could benefit from the deserved assistance and hospitality.

With the descent in Italy of Charlemagne, the Duchy of Parma was transformed into a county and subsequently into a bishop’s diocese controlled by the church.

From the ninth century, therefore, cloistered centers, predominantly Benedictine, encouraged the reclamation of the territory by the inhabitants and allowed a restoration of the agricultural land. The bishops progressively assumed temporary powers and Parma provided two antipopes, Honorius II and Clement III, who brought conflict between the religious and political powers of the Duchy.

The beginning of the Middle Ages in Parma is characterized by lordships, mainly of the families of Suppondi, Arduinici, and Bernardingi. The struggles between the Guelph and the Ghibelline factions involved Parma too, with the prevalence of the latter, although Parma participated in the Crusades in the Holy Land supporting the papacy in 1101.

The internal conflicts between the Guelph and the Ghibellines culminated with the defeat of Federico Barbarossa in 1176.

The constitution of the municipality marked the beginning of the rebirth of the city after a period of Medieval turmoil, and Parma became a free city characterized by a sort of dualism in that the city was animated by the courage to change its choices in the name of its citizens.

In 1253, the same choices led Parma to tighten a peace treaty with Cremona that lasted for almost a century.

The beginning of the fourteenth century marked the beginning of a series of alterations to the property and noble titles that passed from one family to another. Parma was conquered by the Viscounts and the titles were finally given to the Sforza family.

From this moment on, Parma followed the history of the Duchy of Milan until 1500, witnessing Sforza’s imposition through the help of other noble families.

From the sixteenth century, after a period of wars, alliances, and dynastic passages between various European nobles, the treaty of the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis was signed, which divided Emilia Romagna between the Papacy and the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza.

The French controlled the city until 1521, and then the Church took over. In 1545, in an attempt to create a buffer zone between the Pontifical State and the Spanish dominion in Lombardy, Pope Paul III entrusted the Duchy to his illegitimate son, Pier Luigi Farnese, and this marked the beginning of a flourishing period for Parma.

Thanks to the power and financial means, the Farnese family ruled Parma for two centuries. During this time, the city became a mighty capital and was enriched with imposing monuments and impressive artworks.

The territory became one of the most important in the Peninsula, and the city witnessed an important demographic growth. Soon, Parma became one of the most cultured courts of the Italian Renaissance.

Under the Farnese dynasty, the Dukedom of Parma saw the succession of eight dukes under which the city consolidated its commercial and cultural power. The period is marked by the construction of multiple historical edifices, including the complex of Cittadella. Under Ranuccio I, the city distinguished itself throughout Europe thanks to the blooming music and art scenes.

In 1618, the construction of Palazzo della Pilotta was completed, and architect Giovanni Battista Aleotti was entrusted with the construction of the Farnese Theatre.

Odoardo Farnese wed Margherita de’ Medici in 1628, and this brought new air to Parma. Renaissance in the city was enriched by a school of painting, one of the most important of the period.

The Farnese governed Parma until the first half of the eighteenth century. With their extinction in 1731, the Duchy passed to Charles of Bourbon, the son of Elisabeth Farnese and Philip V. Charles was Duke of Parma and Piacenza between 1731 and 1735, until he was crowned as King of Spain.

Following the historical events that involved the whole country in that period, Parma passed from Spanish domination to the French. After the brief Napoleonic period and the redistribution of the royal dynasties, the duchy changed ruler and was entrusted to the Hapsburgs.

Marie Louise of Austria, the second wife of Napoleon, governed Parma from 1816 to 1847, establishing an absolute sovereignty that consisted of non-native ministers. However, her rule brought wealth to the region and the Duchess was so prestigious that the first Risorgimento movements did not affect the Duchy.

In 1847, with the death of Marie Louise, the Duchy returned under the rule of the Bourbon, and in 1860, with the Armistice of Villafranca, the plebiscite declared the annexation of the former Duchy of Parma to Piedmont and then to the Kingdom of Italy.

With the construction of a new unitary state, Parma was greatly affected by the demotion from the head of a state to a simple capital of a province and experienced severe social and economic crises. Since 1879, the history of the city has been tied to the history of Italy, although the particular courage shown by the population during the Resistance period in the fight against the fascism should be highlighted.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Parma saw the diffusion of socialist unions and organizations that strongly opposed the fascist regime that was spreading throughout Italy. The struggle against the regime culminated in August 1922, when Italo Balbo attempted to conquer the district of Oltretorrente.

The citizens, however, were able to ward off the soldiers and the city was awarded a Gold Medal that recognized the military value of the municipality.

During World War II, the city was devastated by bombings and numerous battles that caused enormous damage. The establishment of a zone controlled by the partisans also provoked social damages to the city.

However, thanks to a quick reconstruction and a flourishing economic development in the post-war period, Parma regained its original splendor.

The city started to shine in the food industry and reassumed its position in the cultural and artistic world. Investing in the development of culture and traditions, Parma was chosen as a headquarters for the European Food Security Authority, and in 2015 it was designated a Creative City of Gastronomy by UNESCO.

ARCHAEOLOGY OF PARMA

Erected on a territory inhabited since the earliest times, Parma boasts rich archaeological testimonies gathered in open-air sites and in numerous museums.

An important archaeological site is the Eneolithic settlement of Via Guido Rossi. Dating from the third millennium BC, the artifacts belong to the Copper Age and comprise exceptional housing structures. Among the structures at least nine rectangular buildings that were perhaps temples or places of worship were identified.

In relation to some of these structures, traces of rituals consisting of deposition of large river pebbles and animal sacrifice were also found.

An ancient archaeological site belonging to the Lower Bronze Age is located at the South of Parma in the area of the Eurosia Shopping Center. Here, archaeologists have discovered extraordinary funerary testimonies and eight small burials. The disposition of the tombs is unique in Italy and extremely rare in Europe, being mainly related to ancient burial practices from Eastern Europe.

Noteworthy is also Terramare di Parma, a complex from the Middle or Upper Bronze Age discovered under the historical city center of Parma. This is one of the first Terramare sites to ever be investigated, and recent excavations brought to light a series of structures of ancient dwellings.

The most important museum from an archaeological point of view is the National Archaeological Museum of Parma, which houses important permanent collections and temporary exhibitions. Parmense Paleontological Museum is a must-see for enthusiasts of ancient prehistory.

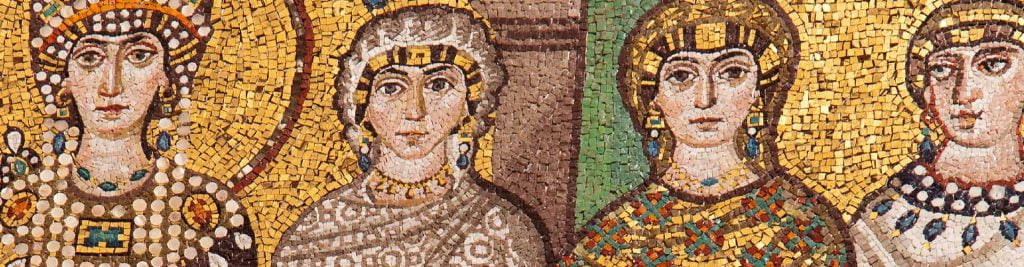

But archaeology can be found in Parma in many places that are neither archaeological sites nor museums. A fine example of the archaeological and artistic blend is the Early Christian Basilica located in Piazza del Duomo. The basilica houses an impressive Early Christian mosaic from the fourth century AD, decorated with interesting Christian symbols.

Travel Guides

The Emilia Romagna Region of Italy

The Cities of Emilia Romagna, Italy