Overlooking the Adriatic coast and nestled in the landscape of the Murgia plateau, Bari is the regional capital of Apulia. Its urban structure consists of two distinct parts, the old city, and the new city.

The former, built on the site of the pre-Roman and Roman Bari, is circumscribed by the ancient city walls and occupies a coastal ledge between the inlets of the old and new ports. Old Bari preserves its medieval appearance and hosts the main artistic monuments of the city.

Modern Bari began to develop in 1813 by decree of Joachim Murat, but only started to expand to its current extension in the mid-nineteenth century. In the interwar period, Bari expanded even further; in this period the Nazario Sauro promenade emerged, flanked by monumental buildings and the new port between the promontory of the old city and the tip of San Cataldo.

Throughout its history, Bari played an important role in the development of the culture in Southern Italy in particular, and on a national level in general. In 1901 the Laterza publishing house was built, which was one of the major protagonists in the twentieth-century Italian culture. The Fiera del Levante was established in 1930. Moreover, the city is an important archiepiscopal and university center.

PREHISTORY OF BARI

The territory of Bari has been inhabited since the earliest times. To confirm this, a skeleton of Homo Erectus was found in Altamura in 1993. But there are many other artifacts that confirm the presence of prehistoric civilizations on this land.

It is believed that the first settlement on which the city was developed was raised in the Bronze Age, and the first peoples to inhabit the territory were the Peucetians, a lapygian tribe inhabiting the areas of Apulia together with the Daunians and the Messapians.

According to evidence, Bari was founded in the fourth century BC and was initially an appendix of Ceglie Messapica, a larger settlement at the time. In fact, Bari only constituted Ceglie Messapica’s outlet to the sea. But the Illyric tribes detached Bari from Ceglie Messapica, transforming it into an autonomous social organism acting as the capital of the territory, called Japigia.

HISTORY OF BARI

Bari was conquered by the Romans in the third century BC, and during their dominion the city established itself as a fishing port and trade center. Rome granted Bari the statute of municipium cum suffragio, which means it had the freedom to establish its own laws and have its own administrative institutions, independent of Rome. However, the city still had to contribute to Rome’s military force and pay taxes to the capital.

The statute of municipality and the strategic location along Via Traiana transformed the city into an important and active pole, attracting merchants and others. The columns on the seafront and an ancient plant located in Piazza del Ferrarese are still visible and are evidence of the Roman period.

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, the Peninsula crumbled and became subject to the invasion of the Goths.

These barbaric peoples descending from Sweden conquered almost all of Italy, including Apulia, and ruled over the territory until 554 AD, when they were defeated by the Byzantines led by emperor Justinian.

Evidence of the Ostrogoth arrival is held by an inscription in a mosaic floor in an early Christian cathedral, which the Cathedral of San Sabino was later built upon.

Under the Byzantines, Bari assumed a provincial character. However, the city established good trade relationships with the military and administrative garrisons in Otranto and Siponto.

The Longobards arrived in Apulia towards the end of the fifth century, and this Germanic people originating from the lower reaches of the Elbe conquered almost all regions and coastal settlements from Bisanzio, including Bari, which was conquered in 668.

Under their rule, the city flourished and became one of the major delineations of the kingdom in short time. With the new leading role acquired, Bari became a sort of capital in the south and established a set of laws, the so-called Consuetudines Barenses, that was used in almost all of Southern Italy up to the nineteenth century, when it was replaced by the famous Code of Napoleon.

The Longobards ruled Bari for almost two centuries, until it was invaded by the Saracens, coming from Egypt. Although the Saracens only occupied Bari for a short time, they transformed the city into their exclusive gateway to the East. The locals, drawn by the new economic opportunities that arose, started to develop their tradesmen skills, learned the art of embroidery and cotton cultivation, and took on much of the Eastern culture, adopting their clothing and fabrics.

Evidence of the passage of the Saracens is scarce, but the Basilica of San Nicola still holds a monogram on the floor that is a clear symbol of the Arabic culture and religion. The local dialect also includes many words related to this legacy.

However, this short period of economic boom that lasted for a mere 25 years, was interrupted by the Longobards who claimed their territory back. This marked the beginning of a rather long period of struggles between various peoples, claiming their supremacy in the territory.

In fact, in 876, the Byzantines defeated the Longobards and established themselves in the area. They made Bari a Catepanato, one of the highest political expressions of the Byzantine Empire and started a robust process of development. Some of the edifices from the era include the Church of Vallisa and the Church of San Gregorio Armeno.

But despite this, Bari still had to cope with numerous raids, especially those of the Saracens. However, thanks to the intervention of Venice, the city was able to free itself from the sieges.

In 1071 Bari was conquered by the Normans, a Scandinavian tribe settled in Normandy, a region in the north of France. Under their domination, the connection of Saint Nicholas and the city was recognized, and his relics were moved from Myra to Bari in 1087. Yet, during Norman domination, the city was razed to the ground by King William I of Sicily who wanted to punish Bari for rebelling against the new dominion.

As a result, all castles and buildings, with the exception of the sacred edifices, were burnt or destroyed. The people of Bari were forced to leave the city and reconstruction only began in 1160, with the ascent of William II of Sicily to the throne.

In 1189, William II handed down the crown to Constance of Altavilla, his niece, due to a lack of direct heirs. Constance was the last Norman ruler in Southern Italy, as her marriage with King Henry VI Hohenstaufen marked the advent of the Swabians.

Constance’s son, King Frederick II, carried out numerous restoration and fortification works in Bari, including the current Frederick gate, the vestibule, and loggia of the Castle of Bari. Under the Swabians, Bari enjoyed a short period of prosperity, which was brought to an end by Charles I of Anjou, who conquered Southern Italy in 1268.

During the government of the Anjou, Bari entered an obscure period characterized by internal and external struggles. The flourishing trade of the city was handed over to the Venetians and Florentines, while many other foreigners looked to benefit from the city’s weakness.

The situation got even worse in 1442 when the Kingdom of Naples was conquered by Alfonso V of Aragon. Under the Spaniards, the lordship of Bari was assigned to Giovanni Antonio Orsini, the prince of Taranto. Due to the strong rivalry between Bari and Taranto, the locals strongly opposed the new administration, which led to riots.

Based on these events, the Aragon handed Bari to the House of Sforza, who helped the Spaniards in the war of succession. In 1501, Isabella of Aragon, wife of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, became Duchess of Bari. The new duchess tried to restore peace in the city, putting forth enormous efforts in helping Bari through this dark period.

Some of her restoration works included the creation of a navigable canal intended to separate Bari from the mainland, linking the city to the peninsula with bridges. However, this attempt never became reality due to a flood in October 1567.

After her death, the duchy passed to her daughter, Bona Sforza, who continued many of the restoration works began by her mother.

However, in 1557, after the death of Bona Sforza, Bari returned under the rule of the Spanish crown. The city experienced a non-hereditary feud and began to sink once again into a dark period marked by abuse, violence, and deception. The population was left at the mercy of the Turks, Saracens and the pirates who roamed the coast, who could easily enter the city, destroying landmarks and taking lives.

This led to new riots and revolts, and in the middle of all this, the plague that struck Bari in 1656 took its toll and reduced the population to a mere six thousand people. The advent of the Hapsburgs did not bring much change. Even though the Kingdom of Naples as a whole began to breathe the air of change under the enlightenment, Bari and its province were left to their own fate.

With the War of Polish Succession and the Peace of Vienna, Bari passed under the government of Charles III of Bourbon. In 1741, after a visit to the city, the new king conceded the restoration of Bari. He approved numerous public works, while his successor, King Ferdinand IV, authorized the expansion of Bari beyond the medieval city walls.

The desired expansion process, however, was never carried out due to political upheavals that had a great impact on Europe and Italy.

During the short existence of the Neapolitan Republic, Bari had a temporary revolutionary government. In 1799, Ferdinand IV reoccupied the throne, but the power of the Bourbon in Southern Italy was already compromised.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Southern Italy was occupied by Napoleon’s brother, Giuseppe Bonaparte, while the Bourbons found refuge in Sicily. Arriving in Bari as King of Naples, Giuseppe assigned Bari’s administration to Joachim Murat, Napoleon’s brother-in-law.

Under Murat’s rule, Bari became a true political and economic power in the region, becoming the capital of the province of Bari, subtracting this privilege from Trani. Moreover, Murat started the expansion work beyond the medieval city walls, establishing a new district which is known today as the Murat district, the heart of modern Bari.

After the fall of Napoleon, Bari returned to the Bourbons, but this time the progress of the city began by Murat continued. One of the most exceptional buildings of the period is the Piccinni Municipal Theater, inaugurated in 1854. In October 1860, Bari became part of the Kingdom of Italy, ending three millennia of foreign domination in the peninsula.

During the Fascist period, the monumental seafront was built and inaugurated as Fiera del Levante. In World War II, Bari became a target of the Allied troops, with serious consequences. Much of the damage included the port, which was quickly reconstructed after the bombing.

In the post-war period, the city continued the expansion begun by Joachim Murat, doubling its residents. But Bari also assumed an important role in Southern Italy. Seen by the European Union as a gateway towards the East, the city developed, improving its trade, industrial, tourism, and agricultural sectors.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Old City was completely restructured, and a profound infrastructural renewal involved the modernization of the port, railway system and airport.

ARCHAEOLOGY OF BARI

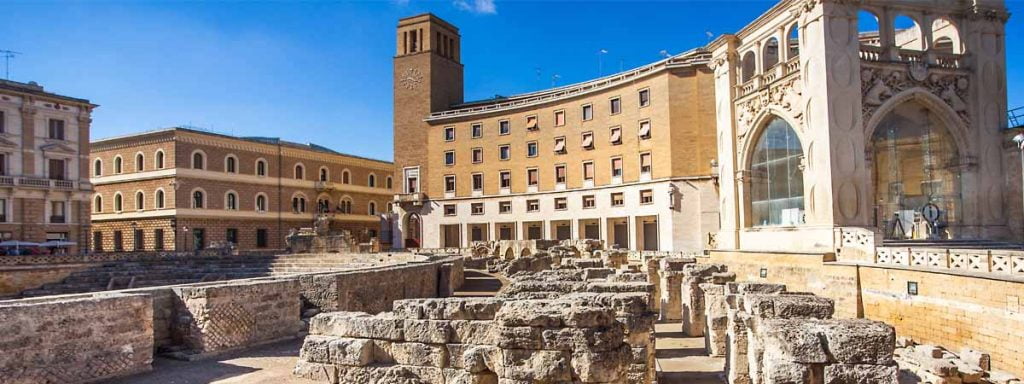

Both the city and the province of Bari hold archaeological evidence. An important archaeological area located within the city is the site of San Pietro. This area is rich in evidence from the Bronze Age, while ruins from the Roman age are also present.

Part of a medieval church and the remains of a necropolis are also present at the site. Above these ruins, a Franciscan monastery was built in the fifteenth century, and its remains are still visible today.

The ruins of Santa Maria del Buonconsiglio are also noteworthy. Located in the heart of the Old City, these evocative ruins consist of a few Roman columns with Corinthian capitals and a precious mosaic floor with octagonal inlays made of polychrome marble and terracotta. The geometric motifs are fascinating, although the floor is not entirely conserved.

Apart from these open-air sites, numerous vestiges are preserved in the various museums of the city. The Archaeological Museum of Santa Scholastica is noteworthy from an archaeological point of view, but artifacts are also housed in the Civic Museum and in the museum housed inside the Swabian Castle of Bari.

Travel Guides

The Apulia Region of Italy

The Cities of Apulia, Italy