Italy, a peninsula stretching from continentalEurope to the Mediterranean, identifies almost all its administrative boundaries with the natural ones.

In the north, Italy stretches up to the Alpine arc, while at south, west, and east, the coastlines and seas represent the boundaries. The neighboring islands of Sicily and Sardinia are also integrated intothis well-defined unit, while the southernmost end of the state’s territory is constituted by the islands of Lampedusa and Linosa, belonging to Sicily.

Despite its morphological unity, Italy only became a unitary state in 1861. Its history is closely linked to the geographical conformation, as the diversity of environments has defined the evolution of the various regions throughout the centuries.

To understand the different growth of the regions it is essential to understand the differences between the country’s territories. In fact, between the northern and the southern sides of the country, there is a distance of about 1200kmor 745 miles. Yet, the Sicilian coast is located at only about 150kmor 93 miles from the African coasts. This explains not only the cultural differencesbut also the diverse history that defines the various Italian territories.

The history of Italy is, in fact, a succession of unions and divisions resulting in the appearance of distinct territorial entities, while the final unification of the country is the result of a long political and cultural process begun in the Roman age.

But despite the common Latin language introduced by the Romans, the cultural identities of the various peoples have always been defined by the local dialects. In fact, the so-called Italian language has been the only language of the literates for centuries, and in the rural areas, most of the locals still ignore it today. Nevertheless, Italy is one of those countries that contributed the most to the history of the world.

Despite its Latin heritage, the name of the country has Greek origins and comes from the term Vitelia, originally used to designate a stretch of Calabria inhabited by the Italics.

A synthesis of the Italian prehistory can only be presented in broad terms. The human presence on the country’s territory is attested since the earliest times, and some of the ancient discoveries date back about one million years.

Artifacts scattered throughout the territory brought evidence of human presence in almost all regions, and some of the most complex findings were excavated in IserniaLa Pineta, in Molise. Characterized by splinter and pebble industries, these relics are attributed to a period about 730,000 years ago.

Acheulean lithic complexes are attested in numerous deposits, and there is important evidence of the Middle and Upper Pleistocene eras. Among the many open-air sites, noteworthy are Fontana Ranuccio in Anagni, Torre in Pietra and Casteldi Guido in Rome, the cave Grotta del Principe near Ventimiglia, the cave Paglicciin the province of Foggia, and other lithic complexes individuated on the island of Capri. Numerous archaic industries have also been reported in Sardinia and Sicily.

Fragmented human remains, belonging to Homo erectus, were found scattered in many of the above-mentioned sites.

The last glacial and interglacial Riss-Würm periods are also very well documented. Remains referring to the Levallois technique, characterized by a standardization of the tools, were identified in many areas of the country. Moreover, numerous remains of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals are also associated with these industries.

Particularly noteworthy are two skulls found in Saccopastore quarries, but also a skull and fragments of two jaws found near mount Circeo, in Latina.

The transition phase between the Middle and the Upper Paleolithic is characterized by the so-called uluzziancomplexes in Apulia and Tuscany. These are perhaps the latest Neanderthal complexes in Western Europe, followed by different cultures such as the Gravettian and Epigravettian phases.

The Epigravettian era is also well-documented. Some of the most important sites preserve traces of important early artistic manifestations, such as those in the cave Pagliccior in the cave Romito, in Calabria.

The Mesolithic didn’t leave much evidence in Italy, but the cultural influences of the Neolithic civilizations brought great innovation to the territory, such as the development of agriculture, the invention of ceramic and weaving, and the beginning of breeding. These cultures were quickly assimilated by the local populations, and evidence of these processes is attested by the copper instruments and the introduction of new tools.

In the same period, the development of trade between the Italian communities and the other Mediterranean peoples are apparent with the phenomenon of social differentiation. Throughout the Bronze Age the affirmation of an economy largely based on pastoralism is apparent, while in the second millennia BC emerged the cultural facies of the Apennines, which were subsequently widespread throughout the whole territory.

In about the same time period the first massive contacts with the Mycenaean civilization are noted, especially in southern Italy and on the islands. The final Bronze Age is characterized by the diffusion of incineration rituals and the progressive formation of cultural facies that will characterize the subsequent Iron Age.

During this period, a division between the peoples living in the plains, dedicated to agriculture, and those living in the mountains, interested in breeding was noticed. This division is responsible forthe subsequent configuration of regional cultural facies of the Iron Age, such as the culture of Golasecca in the northand the Villanovanculture in central Italy.

In the Iron Age was also observed an “ethnic” division of the populations documented by the literary sources from the eighth century BC. The main civilizations present on the territory at the time were the Sabin, Samnites, Iapygians, Etruscans, Umbrians, Italiotes, Mesapinas, and other tribes. Their presence had a great influence in the subsequent Roman division of the territories.

Moreover, the Iron Age also witnessed two massive colonization phenomena, with the Phoenicians in western Sicily and Sardinia, and the Greeks in central-eastern Sicily and in southern Italy.

Italy’s history begins with harsh struggles between the various tribes originally inhabiting the territory. Defeating the weakest, the Etruscans settled themselves in the whole northern region while the Greeks gained control of the south. Both powers were aiming at complete supremacy in the peninsula, and in 535 BC, the Etruscans overcame Magna Graecia, gaining control of the lower Tyrrhenian basin. Nevertheless, a year later, the Greeks defeated the Etruscans and blocked their advancement towards the southin concomitance with the arrival of the Gaul in the valley of Po.

Attacked from two sides, the battles severely compromised the Etruscans and their supremacy in the region, while the upcoming events did nothing but weaken their position even more. In fact, encouraged by the outcome of the battles, the mountainous tribes of the Apennines began to develop an interest in the more developed coastal areas and engaged in battles to gain control over these territories.

The Samnites defeated the Etruscans in Campania, while the Volsci crushed the Latins and the Lucanians gained control over the Greek cities on the Ionian coast.

In the middle of this complex interweaving of clashes, Rome found its inclusion as an active protagonist, and since the fourth century BC fought against all tribes and populations, reaching political supremacy. The Roman supremacy grew stronger thanks to an outstanding military organization and the realistic diplomacy of its rulers, and the system of colonies was established in the conquered territories.

In fact, establishing its hegemony, Rome tightened its political relations by creating alliances and avoiding the implementation of direct control over the conquered territories. On the contrary, the Romans respected the local autonomies, the administrative boundaries and the religious and linguistic culture, facts that explain the loyalty of the people to Rome, but also the permanence and the development of different cultures throughout the territory.

A precondition for the political unification was the affirmation of the Latin language throughout the peninsula. This was not imposed by the Romans but was the result of the official relations established by Rome with the other cities of the territory.

Because of their tactical domination, the Roman Empire gained the loyalty of the peoples, a factproved during the Punic Wars when the tribes of the peninsula remained loyal to Rome despite the idea of independence offered by Hannibal.

However, this unification process experienced a critical moment in 90 BC when a social war burst out because of the agrarian reforms that assigned the control of the lands only to those possessing Roman citizenship. As a result, almost all Italic peoples united against Rome, but the Empire won the battle. Despite its victory, Rome still granted Roman citizenship to the Italic tribes and Augustus included them in the province of Gallia Cisalpina.

An intense development of the urban settlements and infrastructures characterized the Augustan period. This marked a change in the economy with the accentuation of trade between the various regions.

But the flourishing of the Roman Empire stopped under Diocletian and Constantine. The creation of a new capital in Constantinople marked the beginning of the end of the empire, while the assaults of the barbarian tribes fully engaged Rome. As a result of the events, Italy lost its individuality and became one of the most confused territories of the Empire.

The vulnerability of Italy manifested itself dramatically during the great Germanic migrations in the fifth century AD. The Visigoths established themselves in the valley of Po and occupied all the territory to the Strait of Messina, including the Ligurian Riviera.

Between 405 and 406,Tuscany also suffered the invasion of Germanic peoples, while in 452 the Huns further devastated the valley of Po.

In the meantime, in a climate of complete anarchy, the imperial power of the Western Roman Empire entered its final eclipse. In 489, the Ostrogoths invaded Italy under the guidance of Theodore, who was both the Roman emperor and king of the Ostrogoths. The emperor inaugurated the beginning of the Roman-barbaric reign which lasted for about sixty years.

Theodore established a regime of peaceful coexistence between the Romans and the Ostrogoths, with the latter constituting the military and political aristocracy. The Romans, on the other hand, were seen as advisors of a refined culture and were respected for their strong administrative experience, Catholic religion, and involvement in the economic activities.

But the harmony between the two peoples only had a brief history. The incompatibilities between the cultures and beliefs led to harsh conflicts that offered Emperor Justinian a valid reason to intervene in an attempt to restore the Roman unity.

However, the Gothic war brought devastation to the peninsula, leaving it desolated and depopulated by military operations, famines, andepidemics. The territories passed under the direct Byzantine administration which appointed full powers to a magistrate residing in Ravenna.

The imperial authority in Rome was represented by a Duke who shared the government with the Pope. Moreover, the bishops started to acquire authority in all episcopal cities and the Church became the only guardian of the civil law.

In the Gothic era, the Benedictine monasticism established itself in Italy and became one of the most lively and fruitful spiritual forces of the Middle Ages.

But around the same time, the Longobardinvasions extended from Friuli to a large part of the peninsula and marked the division of unity between the various regions. The Longobard kingdom established its seat in Pavia from where it controlled the valley of Po, but also the coasts of Veneto and Liguria, Tuscany, part of Umbria, and the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento.

The Byzantine Empire, on the other hand, preserved its dominion in other regions, such as in Romagna, the Marche, and Lazio, but also in southern Italy.

The Longobard domination lasted a little longer than two centuries, and in this time the Italian population developed and changed in accordance with the progressive civilization of the barbarians. The Longobards exercised their military and political control with the help of the dukes, yet the barbarian population started to assimilate the Latin culture and religion, especially in the time of Pope Gregory I.

In the eighth century, taking advantage of the decay of the Byzantine power in Italy, the Longobards attempted to complete their conquest of the peninsula, but their attacks were inflicted by the popes aspiring to establish their own rule.

In 756, under the Carolingians, the administration of the territories was ceded to the Church and marked the beginning of the Papal State. The subsequent attempts of the Longobards to regain control over the territories failed thanks to the alliance between the Popes and France, leading to the definitive victory of Charlemagne in 774.

As a result, Charlemagne was named king of both the Franks and Longobards and reorganized the kingdom according to the French system, substituting the dukes in the various regions with French counts. The only Longobard duchy that continued to exist was the Duchy of Benevento.

In 800, Italy became part of the Roman Empire reconstituted in the West, while the Byzantines kept control over Apulia, Calabria, Basilicata, and Sicily until 827.

In the ninth century the feudal politics, economy and social structures were consolidated. Nevertheless, the feudal system didn’t find a favorable terrain in the maritime municipalities, where the mercantile economy prevailed. In the same time, the attacks of the Saracens determined a development of the defensive structures.

The popes and bishops engaged in an intense defensive activity that often developed into complex and dramatic struggles against the Carolingians. Under OttoI, the Kingdom of Italy was united to the Kingdom of Germany with important historical consequences.

In fact, the imperial domination of Otto I was conducted according to two fundamental directives, the expansion of Germans towards the Slavic East and towards the Latin South. The political and cultural enhancement of ecclesiastic hierarchies, seen as civilizing forces, led to a unification of the Roman and German political systems and the creation of the great Holy Roman Empire.

This meant the birth of a strong ecclesiastic feudality with the attribution of the political powers to bishops, now acting as lords of the cities. But this phenomenon only interested the northern side of the country, because Otto I left southern Italy to the Byzantines. There were numerous clashes between the two empires, but a marriage between Otto II and a Byzantine princess opened a remote chance for the Germans to extend the house of Saxony to the South.

However, at the end of the tenth century, Southern Italy became a borderland where two rival empires were fighting to achieve their personal interests in the Mediterranean.

It was only Henry II, the last emperor of the house of Saxony, who established more realistic objectives, such as preserving the crown of the Kingdom of Italy to maintain the relations with the Pope and to conquest the Byzantine Mezzogiorno. Under his rule, Italy witnessed a period of development with a growth of population, a flourishing agrarian economy and a strong development of the artisanal production and trade. Yet, this led to social transformation and subsequent tensions between laics and clerics that brought crisisto the feudal order.

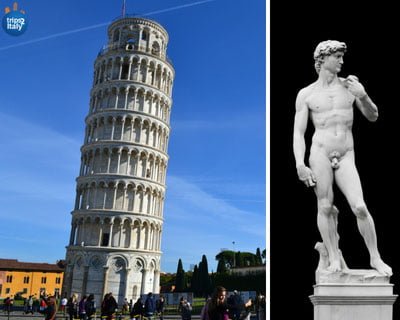

On this background, the most powerful cities started to claim their autonomy. Genoa, Pisa, and Venice laid the foundations of their maritime, military, and trade empires. At the same time, the Normans established themselves in the south and in 1130 unified the whole Mezzogiorno, except the Duchyof Benevento, under the Kingdom of Sicily.

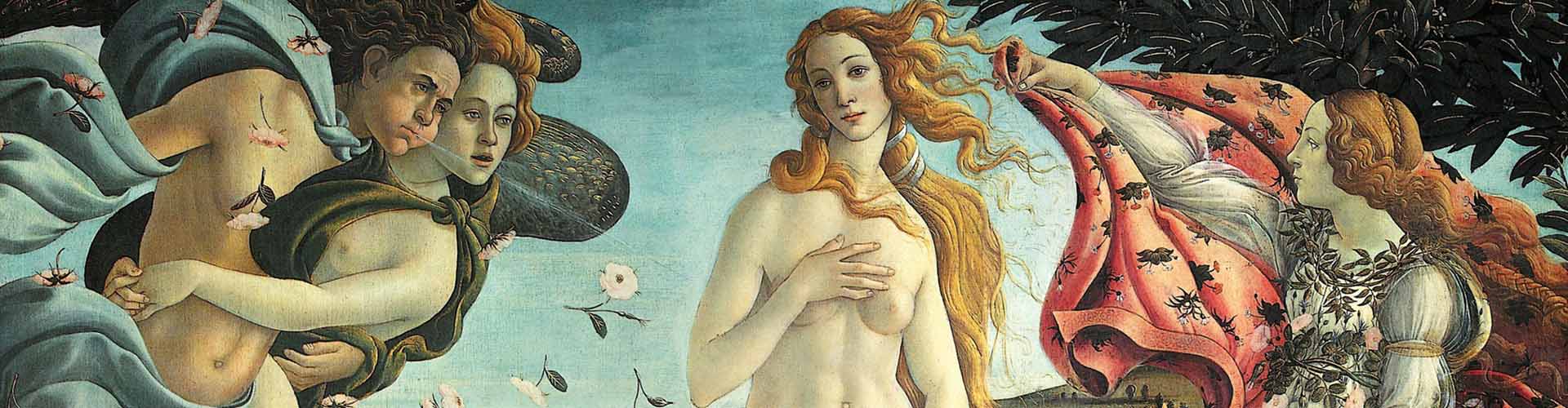

In the following half century, Italy witnessed a profound transformation in the mentality and ways of life which gave rise to new forms of civil coexistence and political activity. In the valley of Po and Tuscany, the noble elites of the cities organized themselves in Municipalities, replacing the bishops in the administration of public affairs. The phenomenon extendedto other regions with the result of an intense economic and cultural development in most urbanized centers.

At the same time, the crusades opened new prospects of commercial, cultural, and political expansion towards Pisa, Genoa, andVenice, but also towards the south. The crusades gradually revitalized the economy of the whole country and contributed to the rising of the bourgeoisie who eventually overcame nobility and clergy, transforming the urban society into a rural one, still oriented toward the idea of Municipality.

With the advent of the Swabians, the country entered a new period of struggles and clashes between the laics and the ecclesiastical powers. The Roman vicissitudes led to agreements between the Papacy and the Empire, with the ecclesiastical power continuously attempting to regain control over all regions. Moreover, Frederick I’s program of imperial restoration opened further hostilities.

In the long war that followed, the Municipalities of Milan, Parma, Piacenza, Lodi, andFerrara formed the first Lombard League. The league played a decisive role in establishing the peace between the Pope and the king of Sicily, which eventually led to the Peace of Constance signed in 1183. Under the agreements of the Peace, the emperor recognized the full autonomy of the cities of the League and only reserved some sovereign prerogatives.

However, only a few years later Pope Innocent III was elected and exercised an unparalleled authority from a religious and political point of view, bringing the medieval papacy to the apogee. The indispensable condition of this uprisingof power was the dismantling of the imperial control in Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria, andMarche.

Yet, under Frederick II, the weak political balance achieved by Innocent III transformed into civil wars that saw the uprising of the social classes. This true social and political progress altered the original constitutional structure of the municipalities, increasing the political influence of a sole magistracy in place of the consuls.

But this period lasted for only a few decades, as Italy entered in the “Guelph age.” This led to a profound crisis and struggles between the Guelph and the Ghibellines. In the middle of all these struggles, the pontiff Clement IV assigned the crown of the Kingdom of Sicily to Charles of Anjou, brother of Louis IX, the king of France. In 1266, Charles conquered the Kingdom of Italy and set the new capital in Naples.

The following centuries saw alternating periods of struggles and development with the papacy and the nobles as protagonists in fighting for power.

The beginning of the eighteenth century found Italy divided intomultiple states characterized by the absolutism of the sovereigns, with a stagnating economy and a widespread misery accompanied by plundering.

Weak and without a political force to represent the national interests, Italy became a sort of object rather than a player on the international scene, while the main European powers were concerned about the country becoming a threat for the continent’s equilibrium.

During the Spanish succession war, Italy was divided into three parts ruled by the Habsburg-Lorraine, Bourbon, and Savoy dynasties. This increased the prestige of the country at an international level, and also strengthened the internal powers. This period of political stability stimulated the development of new economic activities and the flourishing of culture under the influence of the Enlightenment, while the relations with Europe became more lively and continuous. But this also led to the diffusion of new doctrines and reforms inspired by the unequal conditions of the States of Italy. As a result, this enlightened despotism gave rise to an incisive transformation in different parts of the country that constituted distant premises for the Risorgimento.

The first half of the nineteenth century was characterized by numerous struggles under the rule of Napoleon, but a decisive year for the course of history is 1848 that overthrew the existing order and set the premise for the unification of the Italian states.

The personalities involved in the unification process were many, but the names that stand out are Giuseppe Mazzini, an emblem of the liberal movement, Giuseppe Garibaldi, republican and nationalist, Camillo Benso, the count of Cavour, and Vittorio Emanuele II of Savoy, which are four figures who achieved the unification of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

The beginning of the reign witnessed numerous internal struggles, especially in the south, while the whole country engaged in a series of colonial expansion wars in Africa.

The outbreak of the First World War meant the end of the Kingdom and the instauration of the fascist regime. But at the same time, the reunification of Italy was also completed with the reassignment of the northern territories of Trentino-Alto Adige and Friuli Venezia Giulia to the national territory.

The Second World War took its toll on Italy, and the allied armies brought devastation to many regions and cities. The end of the war found the country in critical condition, with the main communication routes interrupted and entire municipalities razed to the ground.

On June 2, 1946, an institutional referendum marked the end of the monarchy and the birth of the Italian Republic. From this moment on, the country entered a period of economic development that interested all sectors, while on a political level, Italy was one of the founders of the European Economic Community, which developed into the European Union.

Archeology in Italy is extremely well represented, and it’s impossible to mention all the noteworthy open-air sites and museums to visit. The most famous from an archaeological point of view is perhaps Rome, a city defined by many as an expansive open-air museum.

Apart from the many outdoor sites scattered throughout the city, there are dozens of noteworthy archaeological museums to mention.

Umbria, Marche, and part of Tuscany and Abruzzo are famous for their Etruscan heritage. There are numerous artifacts documenting the Etruscan civilizations, their ways of life, main occupations and beliefs. Southern Italy preserves many testimonies of the Greek and Byzantine cultures that blended and shaped the evolution of the regions.

On the other hand, the northernmost regions present interesting testimonies of the passage of the Germanic peoples.

Roman vestiges are scattered throughout the national territory, and important artifacts are preserved in the National Archaeological Museums present in almost all municipalities throughout Italy.