Ravenna is a charming town located in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. The town is in the lower Romagna plain and in the southernmost sector of the Po Valley. The city connects with the Adriatic Sea through the Candiano Canal (also known as the Corsini Canal).

The history of Ravenna includes periods of both splendor and decadence, as well as destruction and reconstruction.

The original nucleus of the city developed during the imperial age on an orthogonal plan still recognizable in some areas of the city. An extraordinary political importance acquired in the fifth century is also reflected by the urban structure and famed early Christian monuments, eight of which have been collectively declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Ravenna reached considerable size in the nineteenth century due to expansion towards the north. Though at the beginning of the twentieth century, the city was still partially enclosed within the medieval walls.

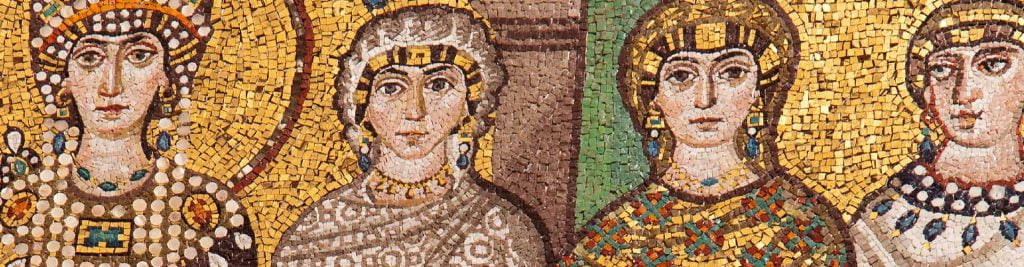

World War II caused severe damage to the city, yet after the war Ravenna entered a period of industrial growth that translated into residential development in 1952. Today, the city is revered as a bastion of culture thanks to its remarkably well-preserved fifth and sixth century Byzantine mosaics.

PREHISTORY OF RAVENNA

The first human traces in Ravenna date from about 3,000 years ago when civilizations from the East established their first settlements in the territory. The first dwellings were built on islets and were connected by bridges, as Ravenna at the time was completely surrounded by water.

During the fifth century BC, the Umbrians arrived in the region, followed by the Celts in the fourth century.

Thanks to the sea and lagoons surrounding the settlement, Ravenna became a wanted territory by populations who desired to prevent access of their enemies. At the same time, the water also provided important escape routes in case of extreme danger.

It is no wonder why Julius Caesar became interested in the territory and decided to build an important military port in the city.

With the Gulf of Naples controlled by the Greeks, Ravenna became an important Roman port through which the Empire controlled the whole Mediterranean. The port housed a fleet of 250 ships and thus guaranteed the defense of the Adriatic and of the neighboring seas.

HISTORY OF RAVENNA

It was in Ravenna that the fate of the Western Roman Empire was decided in 476 AD when the last emperor, Romulus Augustus, was defeated by Odoacer. The Kingdom of Odoacer had a very short life, and Theodoric, the King of the Ostrogoths, claimed control of the city in 493 after a long siege.

The sovereign of the Goths, who died in 526, distinguished himself through a relaxed policy, especially from a religious point of view. The presence of a vast community of Aryan Christians led to the construction of numerous buildings of worship, and the city was enriched with many artworks.

In this period, Ravenna assumed the appearance of a royal city and received a new Basilica. Another important edifice from the era is the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, a monumental building with an impressive marble portico and a cylindrical bell tower erected between the ninth and tenth centuries. The majority of the monuments constructed during this period were decorated with the remarkable mosaics that the city is known for today.

Upon being proclaimed the Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, Justinian I started a political program aimed at reconquering those territories of the Western Roman Empire occupied by barbarian kingdoms, Ravenna included.

After emerging victorious from the Gothic war, Justinian I established a protectorate in the peninsula that was based in Ravenna and controlled by exarchs. Though no longer the capital of a kingdom, Ravenna continued to flourish under Justinian I as a key seaport and important hub for the surrounding area.

Ravenna’s primary golden period lasted until 751 when it fell under the Longobard offensive. Subsequently, by the will of the Frankish King Pepin the Short, under the Pact of Quierzy, the city was passed to the papacy in 754. However, the pact was never fulfilled because the Longobards remained in the city only until 756; after that date the power passed to local archbishops who exercised their privileges with the support of the local aristocracy, recognizing the church of Ravenna as independent from the papacy of Rome.

The privileges enjoyed by the archbishops led to positions of open conflict with the Roman popes who supported the Holy Roman Emperors and the Swabians.

As a municipal order, Ravenna was first controlled by the archbishops and later by the noble families who aspired to the lordship.

The first noble dynasty to rule in the city was the one of Travesari, who exerted their power until 1275. Their place was taken by the Da Polenta dynasty, a noble family who offered hospitality to Dante Alighieri during his exile from Florence. The esteemed medieval poet would eventually die in Ravenna in 1321.

Between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the nobles changed the course of the two rivers Montone and Ronco to create a natural defensive structure around the city walls. This change also improved the agricultural yield of the surrounding land, bringing wealth to the city.

The lordship of the Da Polenta lasted until 1441 when the Venetians claimed control of the city. The Venetians ruled Ravenna until 1509, and in this period the city center was enriched with several Venetian style buildings, including the Rocca Brancaleone.

The city passed under the control of the Papal States in 1509 and was attacked in 1512 by the French army during the War of the Holy League. Ravenna remained under the Papal States for the next 350 years.

In this period the progressive raising of the Ronco and Montone rivers, now flowing around the city, caused several floods. The problem ended only in the eighteenth century, with the deviation of the two rivers that were merged into a channel to the south of the city.

As these natural events unfolded, Ravenna was under the Rasponi family. During 1527 and 1530, the city passed under Venetian rule once again and knew a brief period of recovery, yet the period was too short for the city to regain its lost prestige.

The seventeenth century was mainly characterized by plans to save the city from the waters. The construction of an internal canal and the famous diversion of the Ronco and Montone date back to this period. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, thanks to Cardinal Alberoni, the two watercourses were reunited in a single riverbed and diverted towards the south of the city. In the meantime, construction of the new port and the Candiano Canal also began.

In June 1796 Ravenna was conquered by the Napoleonic troops and – following the Tolentino Treaty – it passed under French domination.

After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Ravenna returned under papal rule, and during this period, the city lived the Risorgimento under Cardinal Agostino Rivarola, sent to Romagna to control and suppress the actions of the Carboneria (secret revolutionary societies) that was taking hold, especially thanks to the action of Lord Byron who declared himself a friend of the patriots of Ravenna.

In the years of the Risorgimento, namely in 1849, the city organized the famous “trafila,” which is a procedure the townspeople created to help save Garibaldi from the Austrians.

The Capanno Garibaldi monument bears witness to the important role Ravenna played in the events of the Italian Risorgimento. The monument is located in one of the most evocative places of the Po Delta Park, about 5 miles northeast of the city, and is perfectly preserved. In 1859 Ravenna was among the first cities to free itself from the papal government and to join the national unification.

The most recent history of the city is characterized by large land reclamation and the emergence of solid cooperative movements. Though Ravenna was severely damaged during the two world wars, the post-World War II period brought rapid industrial and tourist development of the city, and the rebirth of the port, which is one of the major Adriatic ports even today. Though not as famous among casual international travelers as other Italian cities, Ravenna is a dream destination for lovers of early Christian art as well as Roman and Byzantine history.

ARCHAEOLOGY IN RAVENNA

Archaeology is well represented in Ravenna. Traces of Roman and Byzantine villas have been identified scattered throughout the city, one of which is the famous Domus dating back to the sixth century BC. The villa was found in 1993 during excavation works that reconstructed some of the ancient settlements.

Located inside the eighteenth-century Church of Santa Eufemia, in a vast underground environment about 10 feet below street level, is a Domus made up of 14 rooms paved with polychrome mosaics and marble belonging to a private Byzantine building.

Another important site is the Archaeological Park of Classe. This archaeological site contains the port area of the ancient city of Classe, corresponding to the modern southern area of the city located between the districts of Classe and Ponte Nuovo.

This site includes a series of ancient warehouses built along the docks of a canal, overlooking a road paved in Euganean trachyte.

The complex, probably erected at the beginning of the fifth century AD, was built following the decision of Roman Emperor Honorius to transfer the capital of the Western Roman Empire from Milan to Ravenna in 402.

The decision necessitated an infrastructure that was capable of receiving, storing and distributing a large number of goods and food arriving in the new capital.

The archaeological area comprises about 160,000 square feet and was inaugurated in 2015.

The National Museum of Ravenna houses many important archaeological collections, including one of epigraphy and another with valuable sepulchral artifacts.

Travel Guides

The Emilia Romagna Region of Italy

The Cities of Emilia Romagna, Italy